Kindred Kibbo Kift

A group of Post WW1 pacifists launched one of the most out-there subcultures ever to spend a night under canvas. Meet the curious campers of interwar England who were more Beat than the beatniks and much hipper than the hippies…

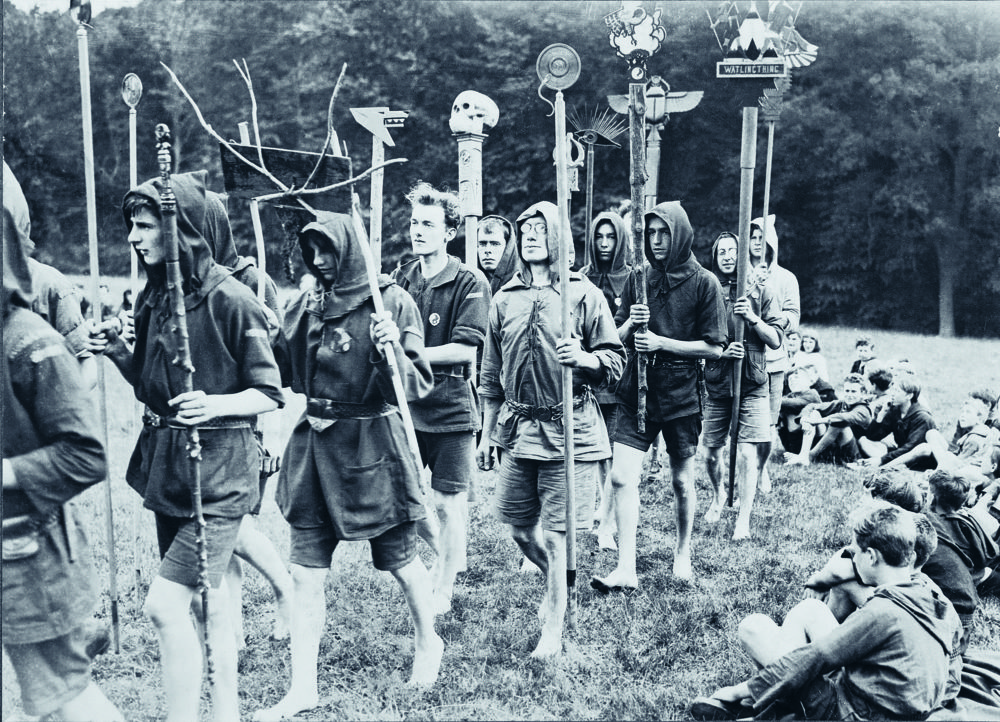

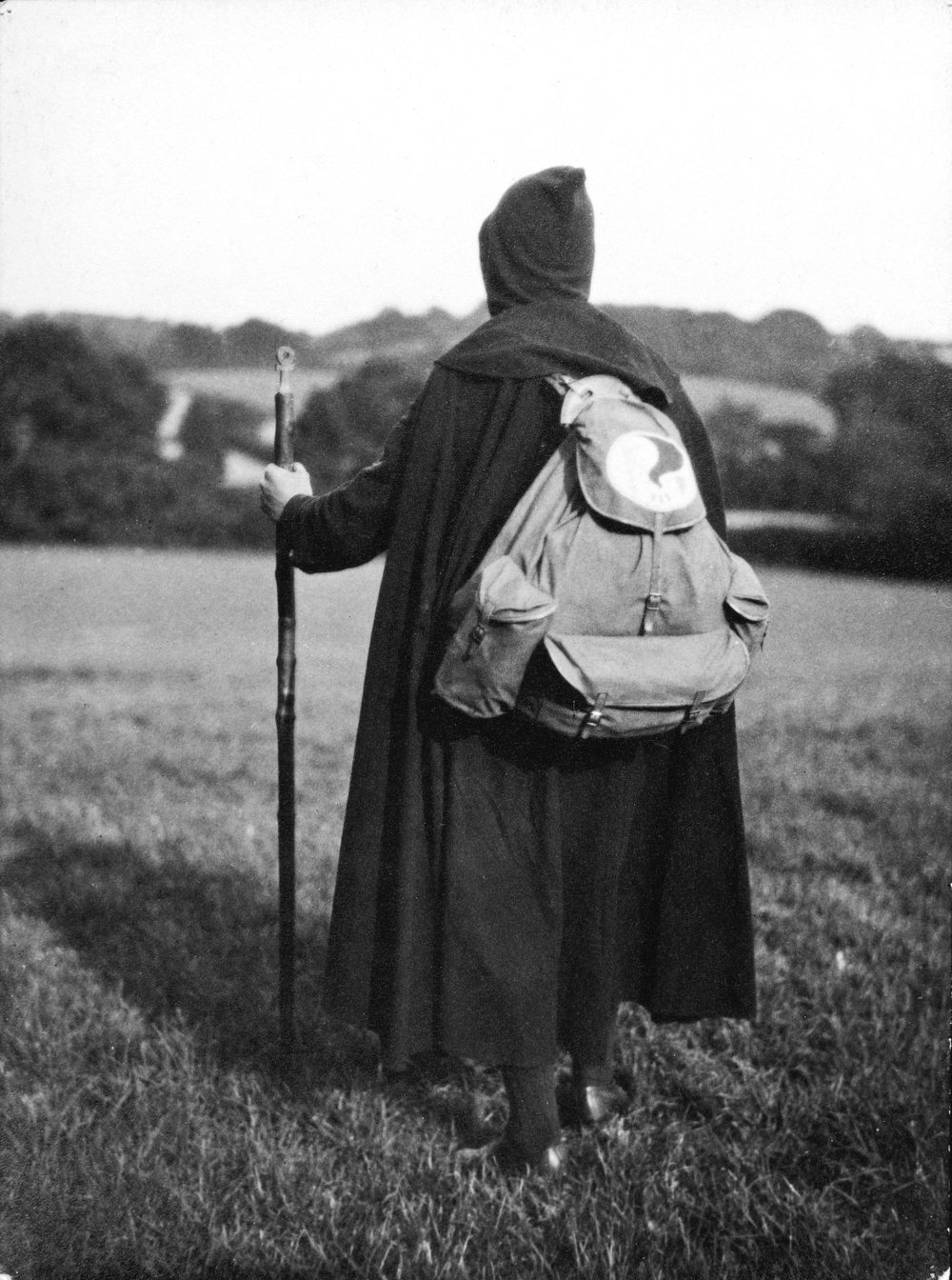

Fortune tellers, foreigners, scouts or priests? The hooded hikers arranged under cryptic banners and marching in triangular clusters caused much consternation among those who passed them in the English countryside in the 1920s. WTF? This was a reaction they relished. From their strange name to their strange attire, the Kindred of the Kibbo Kift cultivated peculiarity and revelled in ridiculousness. As ‘a youth movement for all ages’ that combined elements of mystical religion, political action and avant-garde art, the thousand-or-so members deliberately confused categories.

Kibbo Kift was committed to the outdoor life as a means of counteracting a corrupt urban civilisation, but this was no rural romanticism. With wide-ranging ambitions for total social reform — from education to economics — they sought the complete transformation of everyday life. Members threw off conventional clothing alongside their ordinary names and became instead known as White Fox or Blue Falcon, Batwing or Will Scarlet. They dressed in ceremonial robes and animal masks. The men and women who made up the membership were mostly office workers or teachers by day, but many were also aspiring artists and authors, pacifists, vegetarians and feminists.

Kibbo Kift’s name was taken from an old Cheshire term meaning ‘Proof of Strength’. The group interpreted this in physical, mental and spiritual terms. As such, they searched for radical solutions to the cultural devastation left by the First World War. Contemporary political solutions seemed to them weak and unimaginative, caught up in deathly dull debates in dingy lecture halls. Instead, the Kindred took to the hills in a style that was part performance art and part pagan wizardry, mixing elements both ancient and modern.

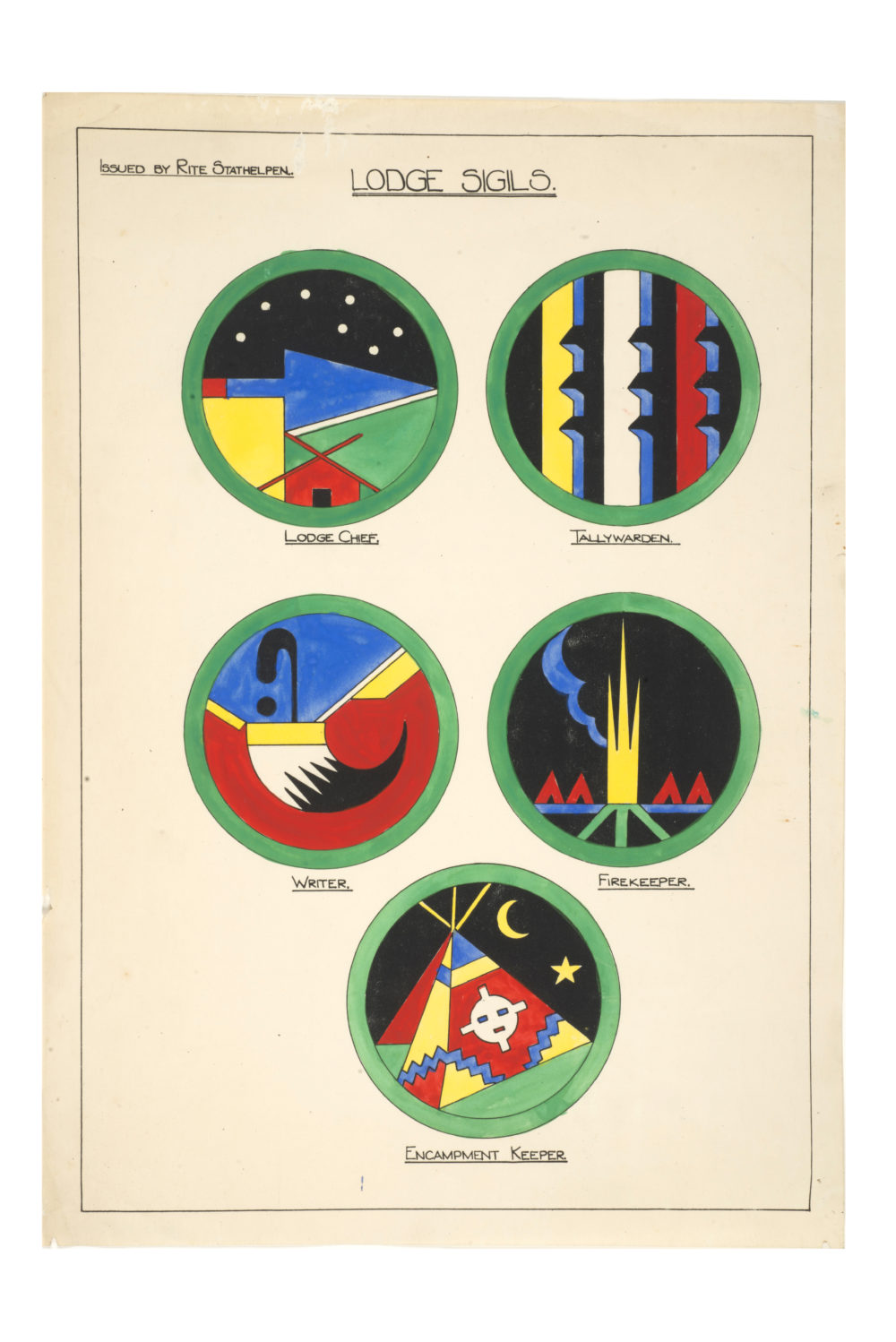

Kibbo Kift’s social and spiritual ambitions were communicated through a wide range of visual media, mostly handcrafted by members. From appliqued flags to painted tents, the group’s colourful aesthetic combined worldwide spiritual influences with English folklore. Images of Beowulf and Robin Hood suggested a yearning for a lost past, but these nestled alongside stylised representations of machines and modernist architecture. Kibbo Kift aimed to return to cultural origins in order to design a new future; this resulted in a caveman-meets-robot chic.

In part these hybrid elements reveal the tastes and background of the group’s founder, John Hargrave. As a former Boy Scout who earned his income through the sale of cartoons and illustrations from his earliest teenage years, Hargrave was informed by the latest commercial and artistic innovations. His father had been a professional artist before him, and he worked among art-school educated designers in the developing advertising industry of the 1920s. Here new ideas about propaganda and persuasion were being explored, alongside early ideas about branding and corporate identity. These influences explain how Kibbo Kift badges and banners incorporated Cubist and Constructivist influences from European and Russian art movements. Hargrave knew what shocked and what sold, and how to make a spectacle that would turn heads and raise questions.

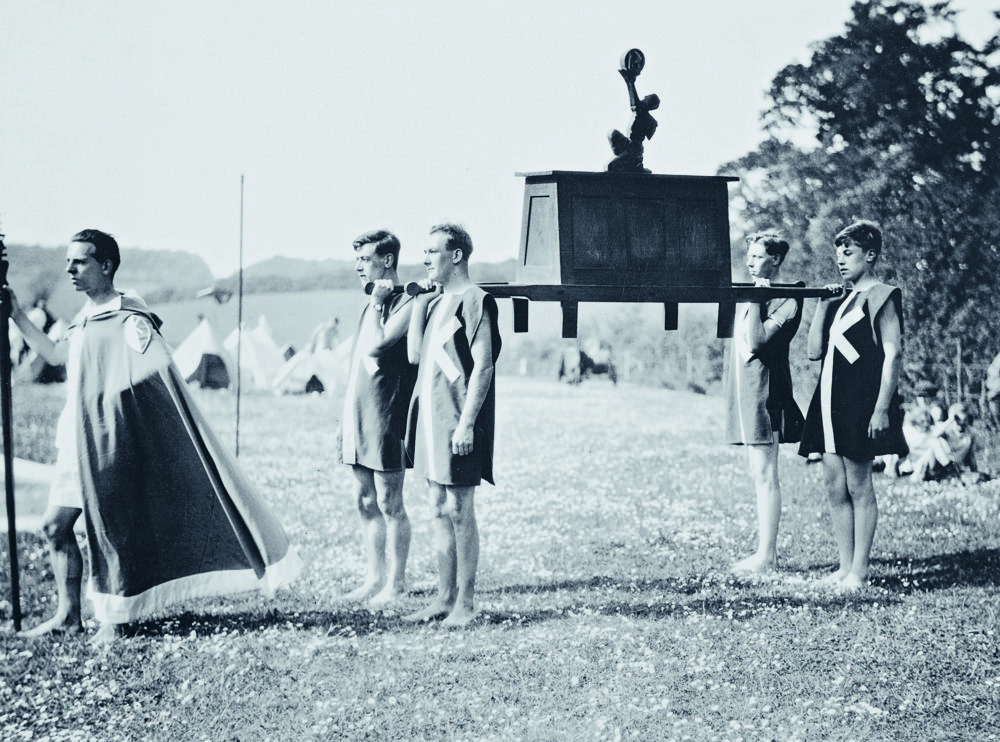

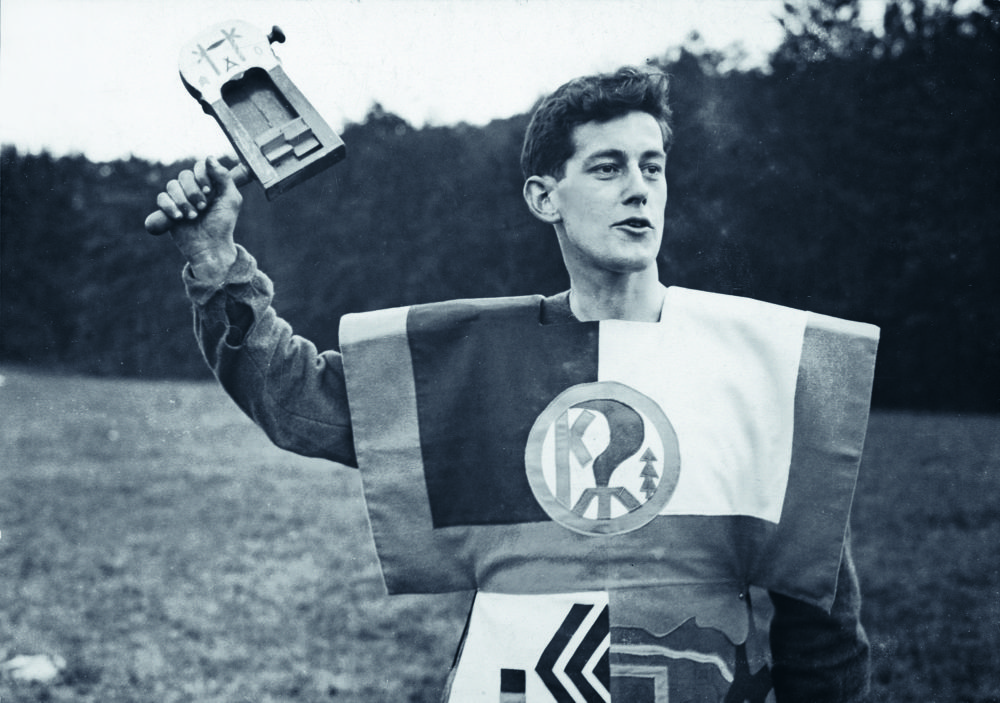

Other members of the group were keen and talented craft practitioners, and those who were not were expected to quickly develop such skills. Advice was given in Kibbo Kift publications about a wide range of artistic practices, from calligraphy and puppetry to weaving and woodcarving. The group’s distinctive camp costume – a green hooded jerkin and shorts for men, and a green one-piece dress and suede headdress for women – had to be individually made by each member to demonstrate their commitment to the cause. When the weather took a turn for the worse, both genders donned a dramatic green floor-length cloak, complete with mysterious pointed hood. The ensemble was finished with a canvas and leather rucksack – also handmade.

Bodily beauty was strongly encouraged in the Kindred through the promotion of healthy living and physical exertion. Group stretches and modern dances were undertaken in the open air in the minimum of clothing. Women exercised in an early version of the bikini, with experimental brassiere cups built from brass or wicker; these were teamed with painted mini-skirts that were highly risqué for the time. Even more daring was the exercise costume for men. Buttock-skimming loincloths and G-strings, decorated with symbols from world religions, which barely preserved Kinsmen’s modesty. Perhaps most striking of all Kibbo Kift attire were their ceremonial surcoats. These square-cut primary coloured robes were worn for ritual circles and singing. Each carried a central circular symbol, designed to communicate — to those in the know — the identity or group responsibility of the wearer, from Herald to Scribe. The back featured Kibbo Kift’s own group insignia, the Mark. This image, combining fire, tree and the sacred K of ancient energy, appeared on buckles, belts and badges as a kind of ancient seal-cum-corporate logo.

Kibbo Kift cut extraordinary figures in the interwar English landscape. They were highly idiosyncratic even in a period when the Scouts boasted a million members worldwide, and when camping and hiking were achieving mainstream acceptability. Mass-manufactured walking boots, waterproofs and backpacks were growing in popularity to support these burgeoning hobbies, and the sight of men, and later women, in walking shorts became increasingly common in the period.

Kibbo Kift’s adaptation of outdoor clothing, however, was never meant as leisure attire and was never designed for mass appeal. They resisted fashion and spurned respectability in pursuit of a new vision for a new future, brimful of new ideas and with a new wardrobe to match. Other pacifist groups have paraded under banners before and since but none has matched the Kindred for the cut of their jib. The world peace Kibbo Kift hoped would come as a result of their camping, craft and ceremony was a dream destined to fail; certainly they were finished as a countercultural outdoor movement by the early 1930s when Hargrave transformed his organisation into an urban economic campaign group.

Such idealism would not be seen again until the Beats emerged in the late forties and fifties, and again when the hippies took up many of the same causes — and plenty of others — in the late sixties. Yet in their uncompromising vision and their dedication to physical and spiritual strength, Kibbo Kift blazed a trail for those who came after. Twenty-first century festival culture and extreme sports adventurers in high performance technical gear both owe a debt — even if most don’t know it — to the curious campers of interwar England.