OUT OF THE BOX: The Rise of Sneaker Culture – Steven Smith Interview

‘Out of the Box’ is the first museum exhibition in America that examines the culture of footwear in detail, exploring what makes it tick, and some of the famous shoes behind the phenomenon. Continuing their great series of interviews with collectors and curators of the exhibition, Curatorial Assistant Lindsey O’Connor sat down with esteemed footwear designer Steven Smith to discuss how he got into the industry in the first place.

‘Out of the Box’ is the first museum exhibition in America that examines the culture of footwear in detail, exploring what makes it tick, and some of the famous shoes behind the phenomenon. Continuing their great series of interviews with collectors and curators of the exhibition, Curatorial Assistant Lindsey O’Connor sat down with esteemed footwear designer Steven Smith to discuss how he got into the industry in the first place.

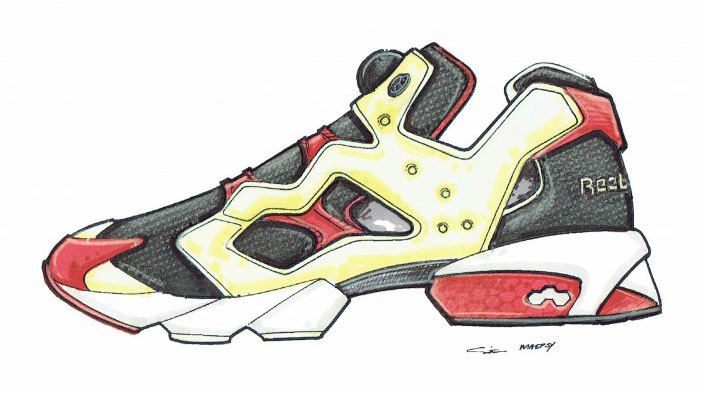

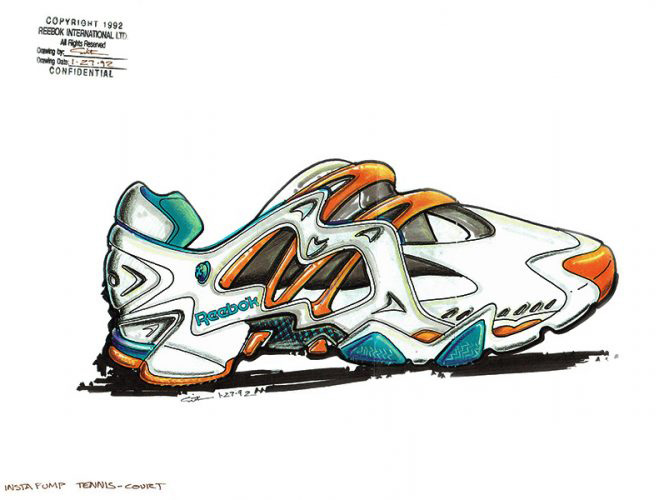

Steven Smith might be best known for his design of the original Reebok Insta Pump Fury, but that’s certainly not the only game changing shoe he’s created. As the third-ever designer at New Balance he designed classic running models like the 675, 676, 574, 995, 996, 997, and 1500, as well as the Artillery and the Phantom 2 during his stint with adidas. Having also worked at Nike, Fila, and Keen, he is easily one of the most prolific sneaker designers working today.

A lot of people in the sneaker industry had a deep connection to sneakers during their childhoods. Was there something in your past that piqued your interest in sneakers at an early age, and what drove you to pursue design as a career?

Back-to-school shopping was important for me. I grew up in a working-class town, and my mom was a school teacher, so with shopping I had to choose wisely because I only got one pair of sneakers. It was a yearlong commitment, so I got kind of obsessed with what sneakers I would choose. Then, when I was 10 years old, my sister started running. She would drag me along, and I developed a love affair with running and running shoes. I started with a pair of Converse: they made a great running shoe at the time. I can remember every pair of shoes I’ve ever owned, and after I was done wearing them, I would save them.

The New Balance 990 became my go-to running shoe; I ran in them all through college. When I was about to graduate from design school, a friend of mine recommended me for a job at New Balance. I interviewed in this old mill with an old-school pattern maker wearing a T-shirt and jeans. The interview went really well. It was getting close to lunch time, and the guy said, “I would take you to lunch, but it’s running time.” Everybody ran every day at lunch, and I was like, “Wow, I’ve gotta get this job!” The next day they offered it to me. The cool thing about working there was that the R&D offices were right above the factory. I love machines, so every day I got to learn something about how to improve shoes and make them better; it was right there in front of me if I had any questions. So in the end, back-to-school season and my passion for running shoes fed into why I ended up at New Balance.

As such a young designer at a major brand like New Balance, how did you deal with that pressure and confront the legacy that accompanies a heritage brand?

It wasn’t that big of a company back then. Two of us were the entire design team, and I designed the running shoes. We would update old shoes so that our products were new and better, not just new and different. There was a lot of engineering involved. I never set out to design something iconic for any company, I just thought, “What’s the best thing I can do at this moment in time with the processes and tools that I have.” It wasn’t about inventing a new process or new tool.

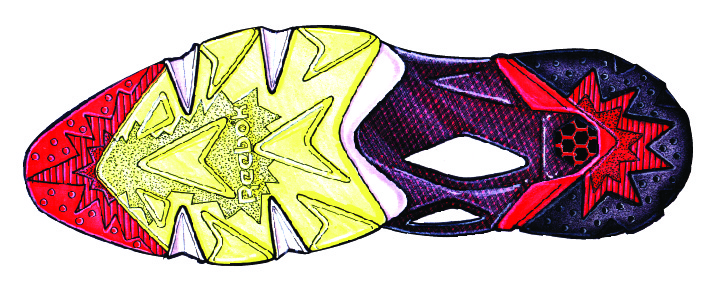

I never intentionally created anything “iconic,” but I guess the closest I came to that mindset was when I was working on the Insta Pump. Music has a huge influence on my design, and I was listening to a lot of hardcore punk. It was all about rebellion, and that’s kind of what the Fury was. Nike was doing so much innovative design, and at Reebok people thought, “Well, why aren’t we doing that?” So I set out to do something radical. The design was like beating someone over the head with a bat, even down to the colors.

It’s interesting to hear that there’s a punk quality to the Insta Pump, and I know you’ve said in the past that while you were developing the product, there was a feeling among the team that you were really on the brink of a major breakthrough.

When I got to Reebok, the first Pump was just about to launch. After that, we began an advanced concepts team to dream up ideas of what the pump could become. We figured that as the inflatable chamber was so interesting, it would be pretty cool if we could just get rid of the shoe. I drew up this basketball shoe with windows and cutouts; the shoe was just the pump with the toe and heel caps. I designed the air bladder first, folded it around a last, and sketched the shoe next to it.

That was a cool project because we used materials outside the sneaker world. The pump bladder was made by a medical equipment company, the carbon arch piece was made by an aerospace company, and the inflator was made by a mountain bike company, so we went almost completely outside the realm of sneakers to make this shoe.

What do you think is the biggest design lesson you learned from working on the Insta Pump?

I learned that it should be uncomfortable for people to look at something new. They should say, “Oh my god, what is that?!” It’s that punk attitude coming through again, but you can draw it, you can build it. So much of the creative process is just dragging people along and slowly getting them to believe in an idea, because at the end of the day, these projects are like your children. I always say “Realisation takes desperation” because a company willing to adopt a radical idea has to be hungry for it. Innovation goes by the wayside when you’re comfortable.

You’ve worked for so many different iconic footwear brands at this point—how do you keep your eyes open for fresh ideas and tailor your designs toward different customers?

Each company has its own DNA, and part of these innovation projects is helping them set the future of their brand. Each brand has its own identity, so you want to work within that and help them grow it. It’s understanding the company and their history, so learning the history of a brand is a key part of designing for it.

You’ve also designed a lot of different types of shoes, so how is it different designing for running versus basketball given the diverse needs of athletes?

I have a hybrid design and engineering mentality. You have to talk to the user and figure out their needs. Having data and a connection to the science side of design is the only way to build something that works. For example, I worked on a lot of Japanese running products. We went to Japan and hung out in dormitories with these high school Japanese runners, picked their brains and saw their lifestyle, and we created a product for them. At the time Nike had this young English runner, Paula Radcliffe, and she wore the product and broke the world records for the half-marathon and marathon. It was great because the product performed for a high school boys running track, but also for a long-distance female runner, so whatever we did worked!

Do you have any other particularly memorable experiences working with people to create specialized shoes?

I created sneakers for Rick Nielsen and Steven Tyler. They both really know what they like, and they both need minimal shoes to run around on stage with. Steven is a great guy and a shoe geek. He used to wear Nike Rifts all the time, so when he’d come through Portland I’d bring a big bag of them to his hotel room. But for the one-off shoes for Rick and Steven, I would use existing midsole and outsole tooling and custom make the uppers: then it was easy to sneak them through the manufacturing system. One shoe that I custom made for Rick was a Nike Presto with black-and-white checkerboard—it had a lot of traction so he could run around on stage and jump on speakers. I made about 10 pairs and gave some to other designers. People thought they were cool any they ended up being sold in Japan.

And now they’re probably on Nike ID…

They definitely are!

You said you listen to a lot of music and punk is really important to your creative process, and you also have a fine art background. Can you talk more about the roles of music and art in your work?

I think art takes many forms and it’s all interconnected. Part of that is being aware and on top of things culturally. A lot of designers like silence to work, but I like it to be as loud as possible—it drives my mind and my hand. My fine arts background is helpful in terms of the history of things and how they’re made. Usually what I do in my personal life and in my hobbies influences the products I create. For a while I’ve been into Mod Culture and Vespas and that has influenced my color palettes. My product design is also influenced by the Bauhaus and Walter Gropius.

Growing up in Boston, Aerosmith was “it,” and it was so cool to see Steven Tyler perform on MTV in the Insta Pump Furys after how draining that project that was. And in those days, it wasn’t like Reebok was giving shoes away to celebrities; he actually went out and bought them. It’s such a cool feeling; you want to thank people for appreciating your design.

Do you feel like there are major differences between the sneaker industry now and when you started at New Balance?

Yeah, it’s really different. There were no rules back then. We built the map to show people how to do things. A lot has become formulaic. You used to see companies come out with products that were really shocking, but now it’s like, “I’ve seen that, I’ve seen that, I’ve seen that.” I want to see something that makes me say, “Holy shit, how did they do that?”

Do you have any advice for aspiring young designers?

Beware of politics! Stay true to your values and the product you want to create.

Also, it’s becoming a tougher industry to be older in. Sneakers are a very youthful product, but no matter how old you are, if you put the right ingredients together you can still create masterpieces until the day you die. I’ve never grown up, per se. I’m still a kid.

And what’s your opinion about the hype around sneaker culture in general?

It’s interesting to see it grow and to see all of these people so fascinated by it. It’s fun, and at the end of the day, what you do should be fun.

And to sneaker fans: wear them! That’s what we made them for!