A Brief History: Flyknit Technology

Material application has always been one of the most important aspects of a shoe, with key properties ranging from structure, durability, comfort; all of which merge together to inform the final styling elements. Adding to an incredibly vast list of technological advances in footwear development over the past 4 decades, Nike continue to push the envelope in creating new materials to add to products across both their footwear and apparel divisions.

The introduction of Flyknit technology in 2012 was another key milestone to add to their material swatch, rethinking ways in which a shoe could be made lighter to allow you to run faster, without running the risk of injury due to lack of support. Bill Bowerman’s philosophy can be traced all the way back to Nike’s beginnings with the waffle racer and his original track shoes, and these technical changes in products over the years have helped take the sporting world to new heights.

Flywire – The Early Stage of Development

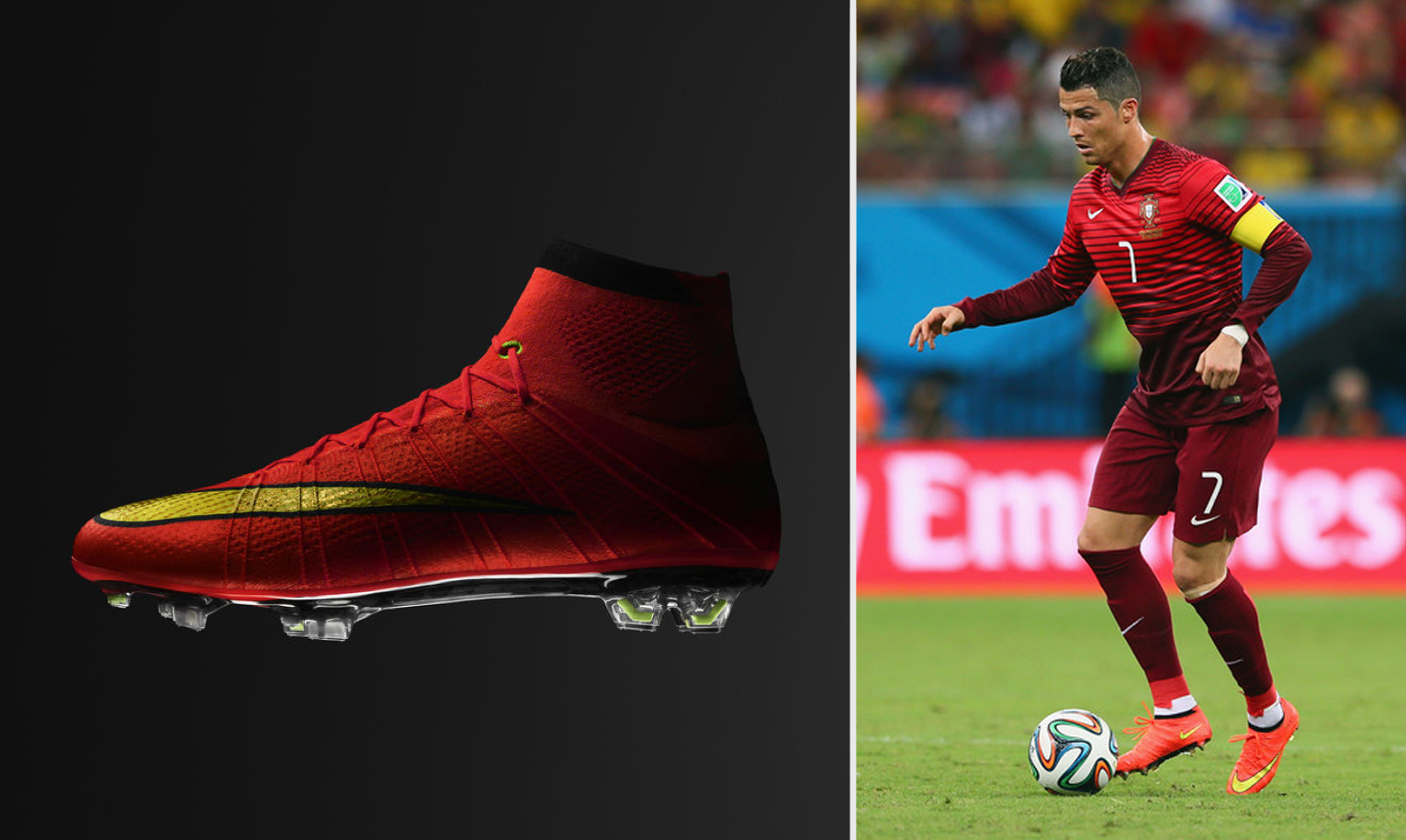

Nike first demonstrated the use of a cable system to aid with support in the form of Flywire technology which was used across a selection of styles throughout the late 2000’s, making an impact initially on the centre stage at the 2008 Beijing Olympics with the Hyperdunk, Zoom Victory Spike & Lunaracer. The purpose was to maintain the strength required to secure your foot while working alongside a thinner layer of material to save on excess weight and hindrance of performance. Years later the support system would lend itself to a myriad of runners, basketball shoes, and eventually onto the football pitch in the form of the Mercurial Vapour Superfly. Around the time of Flywire’s public launch, creatives at Nike’s fabled Innovation Kitchen had already begun trying to improve on this cable concept and exploring how it could be progressively transformed into a material of it’s own. Four years later we witnessed the birth of Flyknit.

Innovation Informed by Past Success

Fast forward to 2012 and the introduction of something unseen. Interlaced materials had been experimented with back in 2000 on the original Nike Woven, toying with the idea of creating a ‘second skin’ with a handmade material for designed for comfort. Over the course of around 195 design reiterations, the Kitchen had created a process enabled to ensure minimal material wastage, the knitting method meant that only a single piece of fabric was being produced to create the entirety of the upper, compared to the 30+ additional material panels which would normally be applied to a runner. The benefits of using automated systems meant for consistency, and the ability to make certain areas on the shoe more flexible than others. Weighing in at around 160 grams, the Racer was approximately 19% lighter than previous marathon level shoes Nike had been producing, and almost half the weight of your average running shoe. The fore-running Flywire system has always been present in the majority of Flyknit releases, adding that much needed support across the sidewalls and holding the shoe together.

Flyknit had taken things to the next level in footwear engineering.

Innovation Kitchen designer Ben Shaffer has previously stated that the key focus areas of consideration for the project were lightness, form-fitting, sustainability, and ultimately performance. The almost ludicrous concept aim was to lose as much of the shoe as possible to most efficiently improve an athletes performance, and the proposed form was that of a sock. This method of minimal thinking paid off, with Flyknit being announced as one of Time magazines Best Inventions of 2012.

The Olympic Introduction

The Flyknit Racer debuted at the London 2012 Olympics as part of the athlete considered ‘Volt’ collection. Designed to cater for the various disciplines across Track & Field categories, each shoe was plastered in a distinct black & neon colour-up, a head turning palette which gained media attention with reports stating that up to 400 competing athletes had participated in the collection. The Racer found its home on the marathon course on the feet of Kenyan long distance runner Abel Kirui who took them to the podium in silver medal position. Special ‘medal stand’ versions of the Flyknit Trainer were exclusively given to athletes from Team USA (with ‘USA’ detailing on the tongue), along with the unmissable full 3M Flash Jackets.

An incredible hybrid which seemed to have gone completely unnoticed by the footwear world, was a pair of Flyknits worn by Kenyan long distance runner Edna Kiplagat. Comprising of a Flyknit Racer upper sitting atop a Lunarlon midsole, a shoe seemingly made specifically for the athlete to cater to her preferences on the road, and something reminiscent of products we’ve seen coming out of the HTM camp.

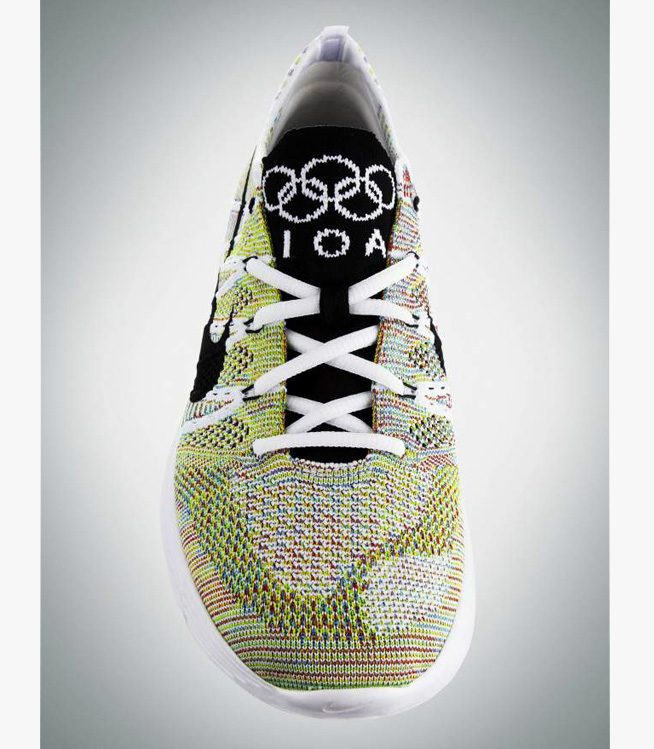

A select few athletes competing in the Games came from countries who didn’t have their own Olympic Committees, and in the case of Guor Marial, didn’t hold a residential passport for any specific country. These competitors were offered the chance to compete under the Olympic flag, and Nike created a special set of apparel and version of the Flyknit Lunar Racer with IOA branding knitted into the tongue.

Further Experimentation

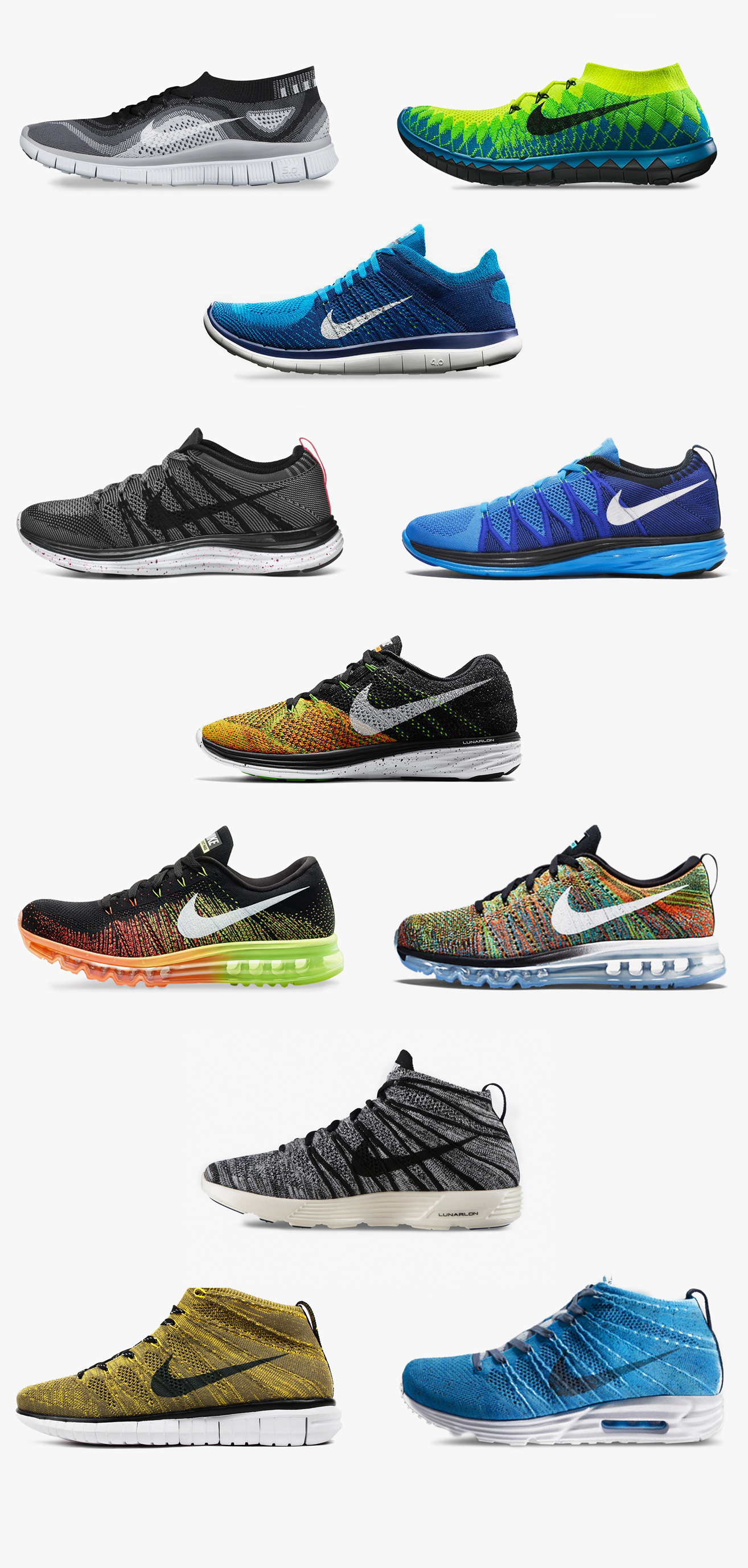

Continuing with their revolution, Nike experimented with various tooling methods to test the limits of comfort. The Racer and Trainer originally sat on a Phylon foam midsole (the same material used on the Air Presto 12 years previously) and progressively tested the waters with Lunarlon, Free 3.0 & 5.0, and eventually at the end of 2013 they took the next logical step and added a full length air unit. Further alterations were made to the upper, and a midtop Chukka style was also released. With Flyknit sitting at the top of the technical running market, the next test was to see if it could hold its own across other categories.

Limited Editions

As with all experimental pieces of footwear, there will always be rare versions which are virtually impossible to get your hands on, and soon become almost unattainable grails that take years to track down. Always at the forefront of innovation, the HTM collective of Fragment Design’s Hiroshi Fujiwara, Nike Vice President for Design Tinker Hatfield, and Nike CEO Mark Parker created several of their own versions incorporating the technology. The majority of the specific models designed have never been put on the market at a general release level (excluding the Lunar Chukka, Free NSW and Mercurial Superfly), and merge a range of different uppers and midsole combinations seen on previous and forthcoming releases. The HTM initiative has always been an incredible platform for testing the waters with product to see what works in the marketplace, with numbers on each release sometimes only in the hundreds.

Onto the next one…

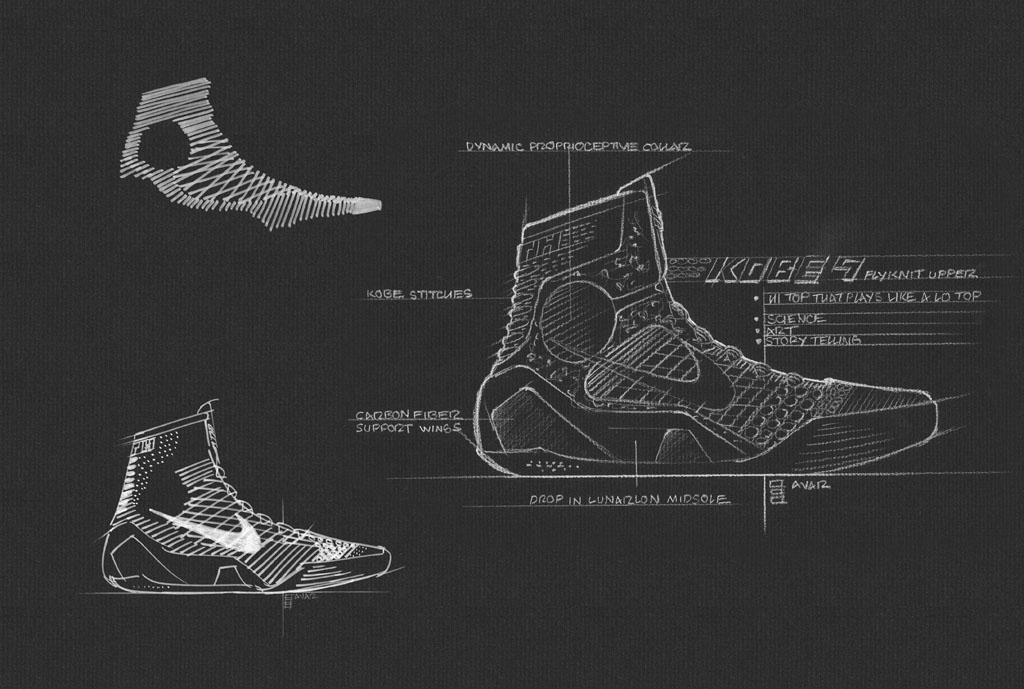

Nike designer Eric Avar had already made an impact introducing new technology into basketball with the aforementioned Flywire addition to the Hyperdunk (and later on the Kobe IV in 2009) and he stepped up once again in incorporating Flyknit into Kobe Bryants ninth signature shoe in 2014, with the knit texture running all the way up the boot structure. This application was in turn rolled out onto his tenth and final eleventh shoe to celebrate the conclusion of his NBA career.

Bringing us up to the present day, Football boots are the latest category to go under the scalpel, with the introduction of the incredible Magista and Mercurial Superfly that have been in circulation for the last year. Both were originally received with mixed opinions across the board, but have since cemented their place as a favourite among players, lightening the load and improving your speed and reactivity on the pitch. Reversing their vision, during the past year Nike have re-appropriated the styling designed for these specific boots, and placed them back onto the streets in the form of the Footscape Magista and HTM Free Mercurial Superfly. This almost ‘tiering down’ of product has been consistent throughout the brands history, products will first and foremost be developed for athletes and elite performance, and then find themselves reinterpreted for street use by the consumer.