Clapton Ultras

Words: Alex King

Photography: Ossi Piispanen

In East London a committed group of football lovers are part of a growing movement of grassroots fans helping the European game rediscover its soul…

A thick plume of bright pink smoke is rising into the air over East London. Just visible beneath the billowing cloud, a man with his face covered by a red shirt is holding a flare aloft. All around him hundreds of fans decked in red and white are jumping up and down, thrusting banners and cans of Polish lager into the air and chanting, ‘No pyro, no party.’ The rowdy mob look like they’re going to burst through the perimeter fence and onto the pitch any second. It’s a terrifying sight for some, but join the Clapton Ultras in The Scaffold and you’ll be welcomed with open arms – whoever you are.

The Old Spotted Dog ground in Newham is an unlikely place to start a revolution. With a capacity of just 2,000, this crumbling stadium is home to Clapton FC, an amateur club playing in the ninth tier of English football. Home attendance averaged just 25 per game until the foundation of the Clapton Ultras in 2012 breathed new life into a faded club. But there’s a much bigger game at play here: the Ultras belong to a growing movement of grassroots supporters helping European football rediscover its soul.

Racist, homophobic and violent politics are on the rise in East London and across the continent. Too often, football terraces expose the ugliest face of politics; whether it’s fans hissing to imitate Nazi gas chambers, throwing bananas on the pitch to mock black players or homophobic chants ringing out in stadiums from Spain to Slovakia. But if skinheads and sexism make you sick, the Ultras offer another way.

Organising in the stands and on the streets, the Ultras are part of an international anti-fascist network. Like their much larger cousins St. Pauli in Hamburg and Rayo Vallecano in Madrid, they’re using football to unite local people to stand up against hate. They’re reaching out to groups terrorised by the far-right, such as immigrants, refugees and LGBT people, to say, ‘You are welcome with us’. Together, they’re fighting for a more positive, inclusive vision of what football – and the world – can be.

English Premiership football has sold out more enthusiastically than any other league in Europe. Wealthy owners lock fans out of decision-making and raise ticket prices while refusing to pay their part‑time staff a living wage. But a fightback has begun.

Clapton is one of many smaller clubs whose fan rank and file have swelled as a result of an exodus from the culture of greed that permeates the upper echelons of the ‘beautiful game’. “Football is a big part of my identity”, says Terry*, a highly committed Clapton Ultra, “but I was falling out of love with it. There’s a total disconnect between fans and modern football. Stadiums are dull: singing’s dead and you can’t even stand up without getting told off by a steward. It’s no different to watching on TV – except way more expensive.”

High ticket prices aren’t the only thing keeping people out of the top-flight stadiums. Though there has been work done by the big leagues to eradicate the more extreme ends of racism and homophobia from touchlines, mainstream football can sometimes still be a hostile space if you’re black, female, or gay. “My old club always made me feel very aware I was the only woman in a male-dominated crowd; they wished I wasn’t there ‘encroaching on their banter space,’” explains Erica, whose visits to Clapton pre-date the Ultras. “Clapton was the first time I didn’t feel patronised or uncomfortable because all the chants were about the players’ mums being whores. I was just accepted.”

Clapton FC was founded in 1877 and it has a long history of welcoming people from all backgrounds. In the early part of the 20th century the club helped launch the career of Walter Tull, who was one of Britain’s first black players and was the very first black British army officer. With each wave of immigration to London, Clapton’s fanbase has kept pace with the changing local demographic. And with East London’s cultural mix more complex now than ever, the club’s ethos has sustained the message loud and clear: people with racist, sexist or homophobic views are not welcome.

After finding a lively alternative to corporate football, this open-hearted heritage convinced the club’s English, Italian, Spanish and Polish fans that The Old Spotted Dog could be a base to build a better football – and the Clapton Ultras were born.

“You truly feel part of a community at Clapton, there’s an unbelievable sense of fun and shared purpose,” Terry says. However, the commitment of the Ultras goes beyond merely waving banners emblazoned with nice slogans. They’ve worked to channel this energy into actions off the pitch, from collecting money for progressive causes at each game to donating to local food banks and running shelters for the homeless. “We’ve been really inspired by seeing how bigger European clubs have harnessed people flooding to football for public good,” Terry continues. “Even with our relatively small numbers, we’ve found you can make a huge difference when you get organised.”

Hamburg’s St. Pauli are one of the world’s most famous clubs — not for their results, but for their politics. In the late eighties, when right-wing hooligan mobs dominated German football culture, local squatters began chanting anti-fascist slogans in the stands, adopted the skull-and-crossbones flag as their unofficial emblem and launched a full punk takeover of the Millerntor-Stadion – embracing the dockers, anarchists, transvestites and sex workers of the nearby Reeperbahn red light district. Today, the ‘world’s most left-wing football club’ is the leading example of what football supporters can achieve off the pitch, from providing housing for refugees to a self-help initiative for fans suffering from clinical depression.

The fact that the Premiership, like most top-flight leagues across Europe, has no openly gay players, gives you a sense of the uphill battle progressive clubs such as Clapton have on their hands to make football culture more diverse and forward-thinking. But the ongoing culture war beyond the stadium gates can seem even bleaker.

Even in East London, the risk of far-right violence is all too real. Clapton’s ground suffered an arson attack after the club made a point of welcoming Asian players in the wake of the 7/7 London terrorist attacks and the Ultras were violently attacked by fascists at an away game in Thamesmead in 2015.

Yet, a continental network of anti-fascist supporters is growing. It includes Celtic’s Green Brigade, Rotor Stern Leipzig and Aks Zły Warsaw, who travel for solidarity matches and share experiences to help inspire one another to stand up against fascism and hold firm alongside their communities. Clapton are decades away from matching the scale of St. Pauli, but what they have achieved in a few years from such humble beginnings shows the power of football to bring people together to make positive change.

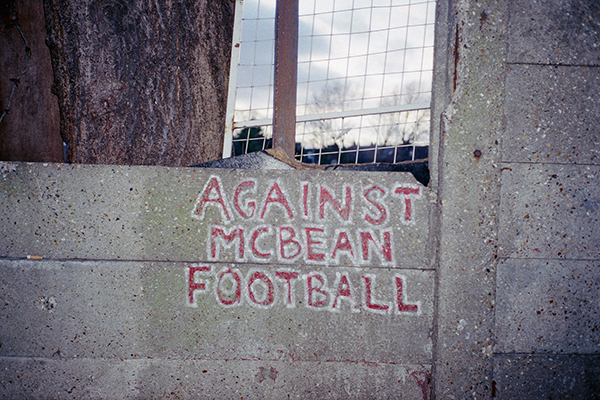

But the fairytale at The Old Spotted Dog might not have a happy ending. The Ultras are currently locked in a dispute with Vince McBean, the club’s owner, and are boycotting home games in protest. McBean has been running Clapton for over two decades, but the Ultras have serious concerns around the running of the club’s finances, and are pushing for fans to take control of the club.

“Local clubs are going bust across the country and their grounds are being turned into shopping malls and luxury flats,” says Erica. “If clubs want to survive, they need to reach out and be relevant to their communities. Football clubs being run purely for profit can’t sustain themselves. We need Clapton to be absolutely transparent, to be run by supporters who are attending games, making noise and who feel invested in this historically important club. Clapton FC will only exist in 5-10 years if it’s run cooperatively by the community. We’re fighting for football for all.”

The billions of pounds flowing through Premiership clubs hides the fact that grassroots football is struggling. With each club that closes, we lose a space where we can remind ourselves there’s more that unites us than divides us. Local football can’t survive without the support of its communities, and each community suffers when it loses opportunities – like football grounds – to create links between young and old, black and white, male and female, gay and straight, believer and non-believer.

Whether or not you care about football, when communities break down and fragment, the only ones who benefit are those who feed off division and mistrust, such as the far-right. Clapton’s revival is a powerful example of the immense positive forces you can unleash when you bring together passion for football, connection to community and hunger to play a part in creating a better world — for everyone.

*Names have been changed to preserve anonymity

“We need Clapton to be absolutely transparent, to be run by supporters who are attending games, making noise and who feel invested in this historically important club.”