Post Soviet Style

Words: Michael Fordham

Photography: Ben Benoliel

There are diplomatic expulsions. There are accusations of killings. Doom foreshadows the Russian World Cup. Brash sportswear is ubiquitous. The Russian aesthetic, which has been channelled to the West via the prism of designers such as Gosha Rubchinskiy, has become hugely influential. In the opening skirmishes of what might be Cold War Two, we ask the question: what’s it like to be young and creative in the Russian capital?

You’re going to Russia they said. You must be mad. The visa process is intrusive enough. Do you have children? Social media accounts? Where have you been these last ten years? As you fill in the forms Insta spies skim your apps. You note some nice New Balance. Next time you look your feed is full of trainers. You do the Macarena in the airport X-ray scanner machine for the crack. 30 minutes later the tune is on the sound system of the terminal’s pizza joint. We’re dancing in the fog of disinformation. We can’t see the edge of the cloud.

Moscow is not Russia

“Fashion is about nowness,” says 22-year-old Andrey Mardo. Andrey is a fashion student at Moscow University. He is six feet six in his trainers and has the lowest BMI in class. He models at the shows in Milan every year and turns up in campaigns for adi and Vetements. We meet beneath the Krymsky Bridge in Gorky Park. It is Saturday morning, fifteen below zero; the sky is ice blue and the light against the frozen river is dazzling. Behind us the monument to Peter the Great towers over us like a marauding Disney baddie rendered by a megalomaniac on acid. Andrey is wearing a tracksuit he made as part of his degree show collection. His gaze is intense. Consonants roll around his mouth. “I take a cut and add something strange,” he says. “I run the line of a zip at an angle. It’s all about asking questions. Why do we need war?” Here below the bridge there’s a series of concrete benches trimmed in hard wood at knee height. It’s a killer skate spot. A uniformed bizzie looks on, swinging a club nonchalantly. “I grew up in a poor family,” he says. “There often wasn’t meat on the table. But now I can travel, I can study fashion. I can be who I want to be. But Moscow is not Russia.” The uniform ignores us. In London we would be hassled for a licence to shoot. Is it our paranoia that makes us feel, straight off the BA flight, that we are being watched?

We can travel, we can eat

“I am not going to vote,” a bald-headed man in his early thirties tells us. We arrive in Moscow early on Friday evening. Wearing all the clothes we own we step out into the brutal night. We walk straight into the first bar we see. The Libertine. Sounds promising. It’s a textured concrete basement. A dozen tables are lit from the side. There are craft ales. There are burgers. Nikki and her oppo behind the bar are long limbed and tatted and pierced. We order a double IPA. Nikki breaks out a bottle of sweet Riga liquor. She pours a shot and we down it. She pours another. And another. Sergei realised we didn’t have a word of Russian. He steps up, orders food for us. He asks us if we’re here to cover the election. I tell him we’re just tourists, honest. The Riga starts to numb my extremities. “I don’t want to be part of an election,” he says. “I don’t want to vote for anybody. And besides, I am going on holiday to Georgia.” Sergei works as a translator in the booming Russian space industry, having moved to Moscow after his first love and his first job for a near bankrupt lower league football team in the south of Russia went belly up. He shares his Insta with us. His new girlfriend is an artist. He travels all over Europe and the rest of the world interpreting for the scientists on the space programme. “But even though I don’t want to vote,” he says, “I know that things are so much better now here than they were. We can travel. We can eat. Our mothers and fathers sometimes were not so lucky.”

Mr Putin is here to protect you

There’s a lot of doom mongering going on about the forthcoming World Cup. If you believe the hype, it’s going to be carnage. Hooligans apparently briefed by some mysterious Putin-led state organisation to attack English fans in Belgium and France for the last Euros confirmed the idea that Russian hoolies were proper. Countless documentaries since then have covered the militaristic gym work, the organised tear-ups in lonely Moscow parks of this almost-militia. The brutalist architecture of Russia provides a handy backdrop to images of a crew of über-thugs ready to pounce on the good olde English, much more cuddly, football hoolie. Undeterred, we plan to go to a Moscow Derby on the Sunday night. Lokomotive versus Spartak. The former are usually the lowly ones, languishing in the shadow of Spartak and CSKA’s dominance. But this evening, they are top of the league.

The fixer on the ground didn’t show. He reckoned we shouldn’t meet up with the Ultras on the day of the game anyway. I buy a Lokomotiv badge, Ben the photographer snags a scarf. The paranoia kicks in again. We’re in the Spartak end. The ultras are singing volubly. Deep, full throated chants, like Iceland in the Euros only more intimidating. There’s an ocean of flags and scarves. There’s an army. I mean an army, of very young coppers. They look cool as fuck in their full-length double-breasted overcoats and furry hats. Metre-long billy clubs swing from their belts. They have callow faces – some classically sculpted, pale and Slavic – recalling the tones and angles of Central Asia. They stand shoulder-to-shoulder, lining the way from the station to the stadium. We guestimate how many of these kids are here. We reckon there’s at least a thousand, just lining this street. Meanwhile there’s a carnival atmosphere in the forecourt of the stadium. There’s merch and food stands. A heated gazebo sells hot tea and non-alcoholic cider. The enormous Lokomotiv of the club’s lore is a totem in the middle of it all. It’s a pleasingly Soviet slice of realism (the club used to be allied to the railway workers’ union). Before kick-off flares and klaxons greet the Loko girls, a madly gyrating gaggle of cheerleaders on Riga and Red Bull. It’s minus twenty. There’s a blizzard. The Loko girls turn it up to eleven. There’s an old lady sitting next to us, also in Lokomotive colours, swaddled in a blanket. I’m aching for a warming cuddle. I can’t feel my feet or my nose. The game moves on apace. The orange ball scuds off the white frozen surface and the tempo is quick against the cold. I strike up a broken conversation with a huge man in a staggeringly garish, full-length fur coat and huge Karl Lagerfeld glasses. He asks where I am from. “I hope you come back for the Coupe Du Monde,” he says, (a bit pretentiously I thought). “You will have fun, he adds. “Mr Putin is here to protect you.” Despite the cold, despite the paranoia and despite the nil-nil draw, it’s a thoroughly brilliant night of football.

I love the idea of colonising Mars

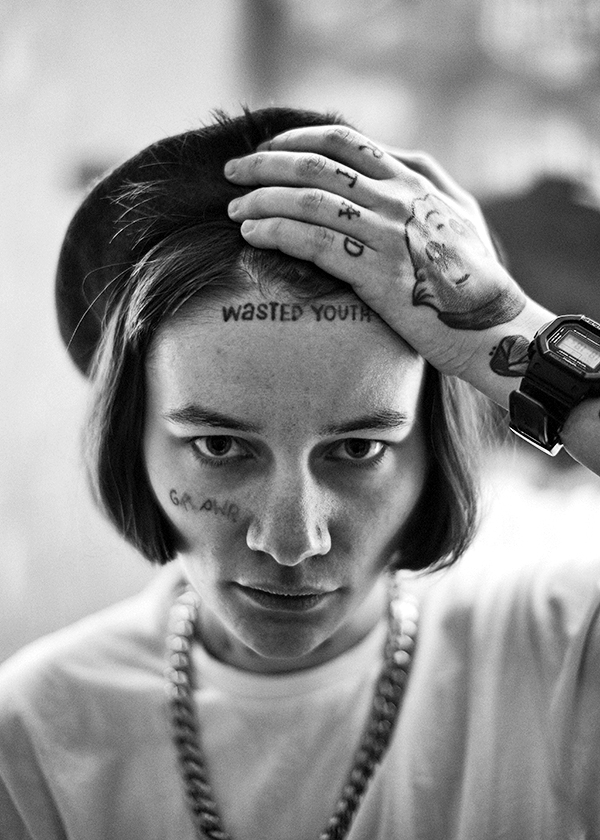

“There is creative space here. Not every niche has been filled,” Daniel Shapovel tells us. Daniel is a 24-year-old studying Fashion Art Direction and has experienced the creative environment in London. “In London everyone seems to have done everything”, he tells me. “Rents are cripplingly expensive”. It is a sentiment echoed by Kirill, who we meet under the bridge in the afternoon. “I like to live fast and Moscow allows me to live fast,” he says. Kirill is a tattoo artist and has mad charisma. “I can see myself staying here in Moscow,” he says. “But who knows. I love the idea of colonising Mars.” On a witheringly freezing afternoon Daniel takes us to The Wine Factory – a post-industrial complex in the Kurskaya area occupied now by studios and eateries. Vanya and Oleg are skaters and creative types. Oleg works with PACCBET (pronounced Rassvet, translates as ‘Sunrise’). The company is a collab between pro skater Tolla Titaev and Gosha Rubchinskiy. If you haven’t heard of this lot, you will soon. “There are many possibilities to express yourself with skating in Russia right now,” says Oleg. “We’re able to do our own thing, create our own look, or own way of doing things. There are big things on the horizon for us, I think.”

There’s a feeling I’m left with. Nikki at the bar doesn’t feel oppressed. Neither does Daniel, Kirill or Sveta. Katrin, the artist and activist, feels gloomy, like she is marking time, but is getting on with things with a kind of calm resignation. Russian youth live with a deep folk memory of political suppression and state surveillance. Now there’s a strong man in charge who fits perfectly the role of patriarch – cast as hero and villain of a drama that is definitive of the times.Russia today might not be the democratic utopia Westerners think everyone should aspire to, but a bad year for a Russian family for a long time meant no food, let alone freedom of expression. Looked at from this perspective it’s not surprising that the people we meet don’t largely seem to feel downtrodden or to be living in fear. But the feeling nags. Would you want to be that guy who, travelling to Berlin, say, in 1936, wrote about a booming economy; an energetic people; a place where everything worked on time and where no one would criticise the state? How would you have interpreted it all? No one wants to be that sort of apologist. If this really is the start of a new Cold War then it is the attitudes and energies and actions of these young people that is going to define at least a bit of what the future holds. It’s in their hands. As well as ours.