How Carhartt WIP became a subcultural phenomenon via Dazed

In anticipation of the long awaited Carhartt WIP Archives book published by Rizzoli, Dazed took a moment to examine the ways in which the brand elevated itself to the lofty heights of streetwear royalty.

On the 8th of August 2011, the staff at the Carhartt WIP outlet on 18 Ellingfort Road in Hackney received a phone call from looters telling them, out of courtesy, that they should vacate the premises. They did. Within the hour, the corrugated metal shutter was ripped open from the bottom of the steel door frame, as a group of mostly teenagers streamed in and out. Out front sat a red Mazda convertible, its roof crumpled like paper, its windscreen a spiderweb of cracks, as smoke filled the driver and passenger seats before the car eventually went up in flames.

For the disaffected youth of London that summer, what started as a protest against the killing of Mark Duggan at the hands of police officers quickly became a retaliatory act. By the time these photos were taken, it had been over 48 hours since the first brick was thrown in anger, and the protest had transcended its original purpose, resulting in a state of dystopian lawlessness that would continue until August 11th.

There was a spate of stores that were looted over those five days – for most owners, emotions ranged from fury to despondency. But in some ways, for those that worked for Carhartt WIP, as they watched images of thousands of pounds worth of stock being walked out the door of their Hackney outlet store, those feelings were likely tempered by a sense of affirmation (some time later, the brand released a t-shirt with the now-iconic photo of their storefront mid-looting). As a brand that, for the past 30 odd years, has been synonymous with differing facets of youth culture, it would have been more of a disaster had the swathes of kids descending on London Fields that day decided they had nothing worth stealing. In many ways, it was a backhanded compliment, a gesture of appreciation for the brand’s work. It’s a label that, many clapping eyes on that distinct, chunky yellow ‘C’, have wanted to be a part of – even if they didn’t quite know why. For Carhartt WIP, this is the way it has always been.

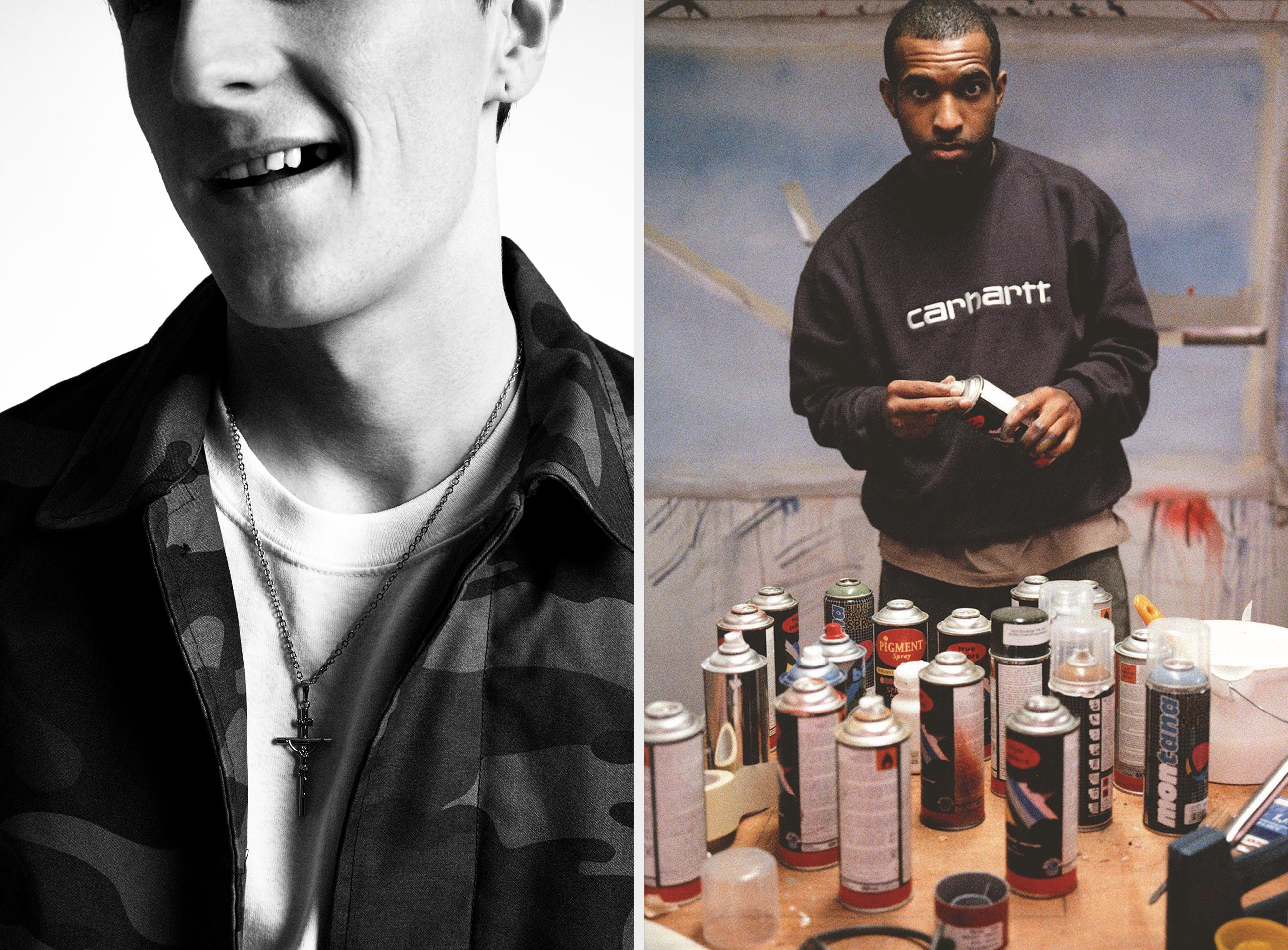

From skaters to musicians, rappers to graffiti artists, that “C” of Carhartt has been subtly omnipresent subcultural signifier over the past three decades. How did humble workwear label become a hallmark of the niche, the subversive, the unusual and the exciting? It is this history of the brand that editors Michel Lebugle and Anna Sinofzik have dedicated the last 18 months of their life to sorting, editing and condensing at the behest of the brand, creating new Rizzoli tome The Carhartt WIP Archives – billed as “the first extensive look into the evolution of an icon.” We met Lebugle in London, and got a deeper look at the book.

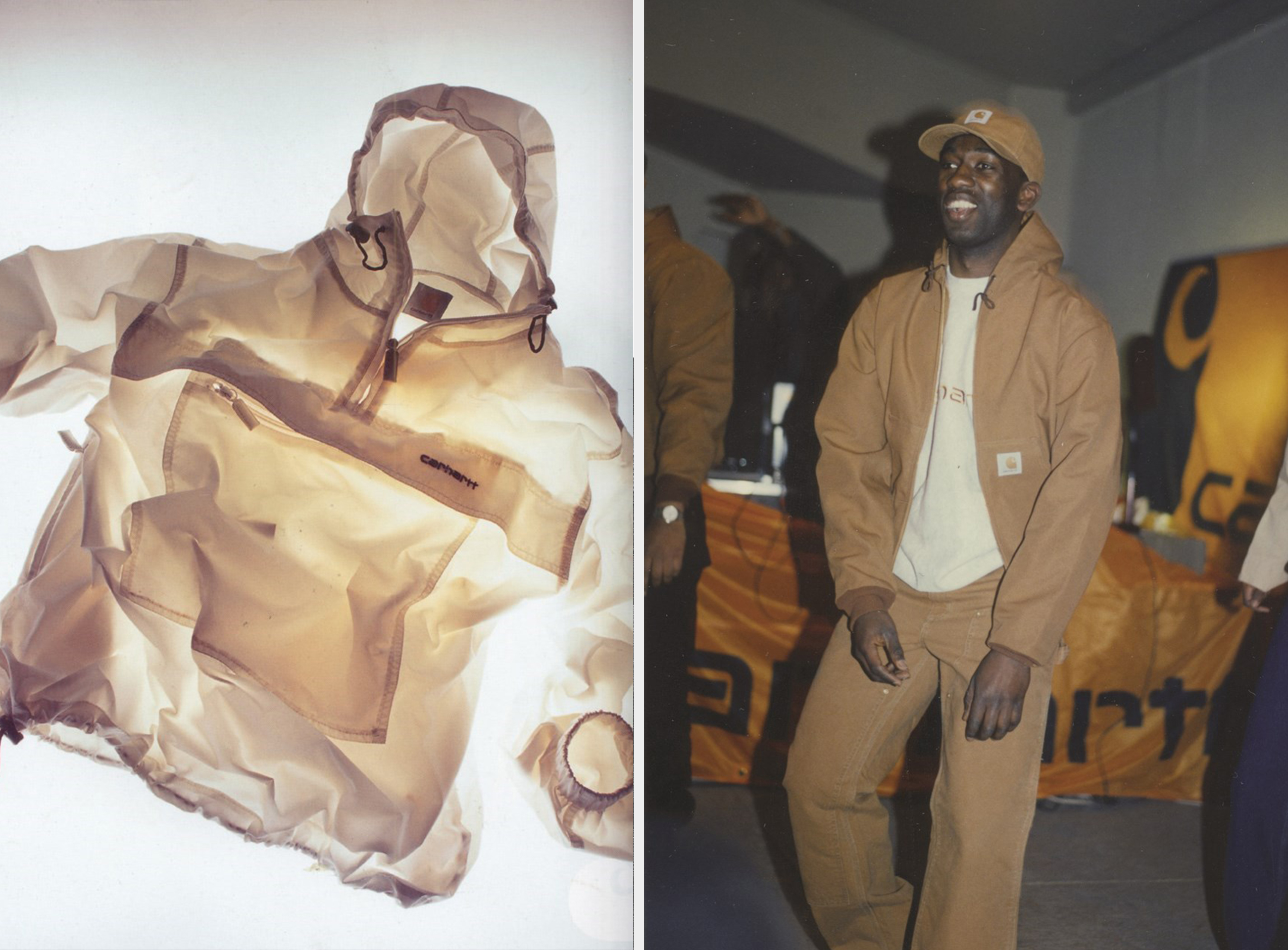

The book starts where Carhartt WIP (Work In Progress) started – in 1989, with what was initially a small-time licensing agreement between Work In Progress, founded by Edwin Faeh, and Carhartt USA, the historic workers’ brand born in Dearborn, Michigan some 100 years earlier. Based in Europe, Carhartt WIP has been responsible for aligning its Michigan-based parent company with the current cultural zeitgeist for the past two-plus decades – which makes it all sound slightly calculated and corporate, but it’s not. Indeed the book documents the building of a brand from its earliest and perhaps least glamorous days, from its first lookbook, shot in their own apartment and modelled by “a local weed dealer and friend.” But it also illustrates how the label has infiltrated the upper echelons of fashion, featuring a glamorous 90s editorial shot by Mario Testino in Vogue, which included a translucent Carhartt WIP windbreaker. It is an infiltration that has, in many ways, been unintentional, for the brand being “too fashion” is something that is to be avoided. The other, as any Carhartt WIP employee will tell you, is the word “marketing”.

“Back then, we called it Marx-iting,” laughs Lebugle. “We would give away money just to do good stuff, instead of paying big amounts to buy you in somewhere. If there was a musician we liked, we just gave them clothes. Maybe later in their career when he wanted to do something else, we’d sponsor the project and just put a little C on it, just a small one.” That prevailing attitude has seen them make abstract films about British adolescence with filmmaker Joshua Gordon, work with Detroit rapper Danny Brown on an exclusive capsule collection to be worn on-stage on during his most recent tour and send photographer Alexander Basile on road-trips armed with a bag of clothes and a camera when they were in need of some accompanying images for their unique brand of “Marx-iting”. The latter resulted in a book and a film in 2007 entitled Dirt Ollies, which documented a skate trip around Mongolia, featuring Basile, Pontus Alv and Bertrand Trichet.

The popularity of Carhartt WIP has always been spurred on somewhat by stateside rappers’ appropriation of their parent label’s workwear – it has been worn by everyone from Tupac to Kanye West, spanning several epochs of the musical genre. In the 80s and 90s, the styles and shapes were overblown to the point it would put Vetements to shame (the two actually collaborated on an oversized overall for the French label’s multibrand SS17 show), tying in with a more general trend for loose silhouettes and sagging pants. “I’m bigger now than I was in high school, but my old Carhartt jacket is still two to three sizes too large,” wrote seminal music critic and rap fanatic Jon Caramanica in The New York Times last year. But as the trend for extremely baggy clothes dissipated within hip-hop, Carhartt WIP had already begun to meet this need. They reduced the proportions of traditional staples to make them more appealing to your average consumer, and began to produce their own designs in 1996.

While the jackets and jeans of Carhartt WIP became less voluminous, they maintained their ruggedness. There has always been something special about wearing-in a rigid, duck brown canvas chore jacket, watching it soften and patina over time. It was this, their garment’s ability to get fucked up but still look fresh, that saw it appeal to skaters and graffiti artists alike. And much like many subcultural staples, the charm of Carhartt WIP, with its minimal branding, was that it allowed the wearer to impart their own identity onto the garment. “The first time I saw Carhartt in was in high school when a friend had moved over from Seattle and wore an American Carhartt jacket – he was hugely into the Onyx/Gravediggaz hip-hop stuff at the time,” remembers Steven Vogel, who would go on to write the seminal book Streetwear. “Fast forward a few years to around 97-98, I was working and skating in London. The drummer that played in the same band as I worked the Carhartt WIP store – and Carhartt essentially had hit a home run at that time when it came to tapping into a functional, minimalistic aesthetic that appealed to me and a few other cats that I used to skate with. They tapped into what I wanted more than anyone else at the time. Looking at what I am wearing today, they clearly still do.”

There was also a spot of fortuity along the way, Lebugle admits – perhaps it was luck that they had earned. By not pursuing traditional marketing campaigns, Carhartt WIP maintained an authenticity that resonated with youths throughout Europe, which ultimately gave them one of the book’s most iconic images. It is an image that most of us that have ever owned a Tumblr will have seen – three young men from the banlieues of Paris, taken from the 1995 cult-classic film La Haine directed by Mathieu Kassovitz, one with a simple Carhartt beanie on his head. The film has been celebrated both for its profound, raw portrayal of life in the Parisian suburbs but also its effortless style. The release of the film saw an explosion of the brand’s popularity in France beyond, but “it wasn’t engineered – this was the reality,” maintains Lebugle. “It’s what people in Paris were wearing at the time – it wasn’t a costume. I think it’s iconic because it’s real.”

In many ways, the weighty tome that Lebugle has produced together with Anna Sinofzik is an unintentional crash course in how to build a burgeoning streetwear brand from the ground up. Carhartt WIP, is of course, bigger now – lookbooks are no longer shot in their graphic designer’s apartment (although don’t rule it out) and they command impressive collaborations with the likes of the aforementioned Vetements, Patta, A.P.C., PAM, Junya Watanabe, NTS Radio, Undercover by Jun Takahashi and Japanese streetwear label Neighborhood and Uniform Experiment – but for Carhartt WIP, it has never been about chasing the customer. Which is why rappers like Action Bronson still reference the label, why skaters still wear it and, occasionally, why hordes of teenagers will rip off a shutter and take some of it without paying – call if Marx-iting if you will. “I’ve always said the Carhartt didn’t choose the culture, the culture chose us,” says Lebugle – it is a sentence that would be met with scepticism if it came from most brands, but not here.

Keep your eyes peeled to the blog for more information on the release of the Carhartt WIP Archives at size? in the coming weeks…