A Brief History: Nike Cortez

Its name changed four times in less than two years, resulting in a moniker that warned a certain German Goliath that David had arrived. But most importantly, even before Nike was a company, it represented the roots that have nourished more than four decades of Nike’s footwear design tree: CORTEZ.

Its name changed four times in less than two years, resulting in a moniker that warned a certain German Goliath that David had arrived. But most importantly, even before Nike was a company, it represented the roots that have nourished more than four decades of Nike’s footwear design tree: CORTEZ.

When Bill Bowerman took the helm of the University of Oregon’s track team in 1948, he quickly began looking for ways to give his “Men of Oregon” a competitive advantage. He wrote many of the leading athletic footwear manufacturers, including adidas, Puma and Brooks, among others. Each was eager to sell shoes to Bowerman, but not so willing to listen to ideas about making running shoes better.

So he began cobbling his own running shoes, trying a variety of different materials and designs. He enlisted some of his Oregon runners to wear-test the shoes and provide feedback, including a young miler from Portland named Phil Knight.

After Knight graduated from Oregon in 1959, he earned his MBA from Stanford University in 1962. At the time, German sports shoes were increasing in popularity in the USA. The shoes were high in quality but rather expensive. Knight saw opportunity here, and turned it into a paper that would have vast repercussions on the athletic and sports industries. The thesis: “Can Japanese sports shoes do to German sports shoes what Japanese cameras did to German cameras?”

Knight made the case that they could, and while visiting Japan in November 1962, he persuaded the Onitsuka Co., maker of Tiger athletic shoes, to permit Knight to be its western U.S. footwear distributor.

Knight received his first Tiger footwear samples in December of 1963. In January 1964, he approached Bowerman, hoping to sell his former coach some shoes and use Bowerman’s endorsement as valuable marketing clout. But Bowerman realized Knight’s association with Onitsuka could provide access to a footwear manufacturer who might listen to his design ideas. So in addition to buying shoes from Knight, Bowerman suggested the two become partners and Bowerman would supply Knight and Onitsuka with his design innovations.

At the Cosmopolitan Hotel, across the street from Portland’s Memorial Coliseum, the two men shook hands on their partnership prior to attending an indoor track meet on January 25, 1964. Blue Ribbon Sports was born. (For more on that fateful day, click here.)

Four months later, on May 25, Bowerman wrote to Onitsuka: “I hope that your arrangements with Mr. Knight would be such that I would be free to turn over the ideas that I have worked out on track shoes.” Little did he know how much his ideas would define the course of footwear history.

After a summer of tinkering on his shoe designs and training his athletes, Bill Bowerman and his wife Barbara headed to Tokyo in October for the 1964 Olympics Games. Three of Bowerman’s Oregon runners competed in the Games, and afterward, the Bowermans stayed an extra week so Bill could meet Kihachiro Onitsuka, founder and president of Onitsuka Co. The two established a relationship of trust and admiration, and Bowerman gained confidence in the Japanese shoe-making process.

Bowerman explained his shoe ideas and toured the factories where his innovations would eventually come to fruition. During the visit, he also connected with S. Morimoto, another Onitsuka leader, with whom Bowerman would correspond frequently regarding designs and the results of footwear testing back in Oregon.

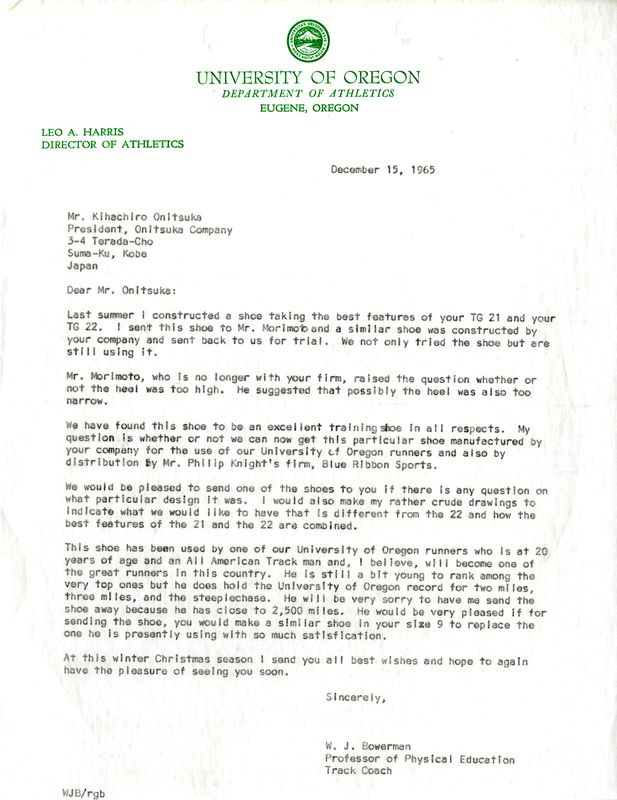

In June of 1965, Bill Bowerman sent Onitsuka “instructive letters and samples” for a shoe that was a cannibalized model of the TG-22 Road Runner and the TG-21. The components of the shoe included the TG-22’s soft sponge rubber in the forefoot and top of the heel, the TG-21’s hard sponge rubber in the middle of the heel and hard rubber used on the outsole.

On July 25, Morimoto wrote back stating that he received Bowerman’s letters and samples and was sending a training shoe built to his specifications. However, Onitsuka had “some opinion as to the inserted sponge rubber at the heel.” Despite Onitsuka’s objections, Bowerman continued to believe in the placement of sponge rubber in the heel, stating that it would help alleviate Achilles tendon issues. Eventually, the feature would become a major selling point for the shoe model.

On October 14, Bowerman wrote to Morimoto: “The shoe that you made for me in July is above my expectations in all respects. It is a better shoe than I had hoped for.”

Bowerman was referring to—but not identifying—Kenny Moore, who would go on to become an Olympian and an award-winning sports journalist and author of several books, including the biography Bowerman and the Men of Oregon, published in 2006. Thanks to the book, Moore’s contribution to Bowerman’s innovations has been revealed. And his story represents the genesis of Nike’s practice to always put the athlete first.

In the spring of 1965, Moore was injured during a University of Oregon track meet when he moved wide and was stepped on by his passing teammate. The teammate’s spikes tore through Moore’s Bowerman-made shoe and opened a gash that required seven stitches. For two weeks leading up to the Pac-8 Conference Championships, Moore could barely train. Heroically, he recovered and won two events at the Pac-8 meet, helping Oregon to the team title.

The next day, defying Bowerman’s wishes to take it easy, Moore took off on a long training run but had to stop suddenly, seizing in pain. Moore discovered he had suffered a stress fracture across the third metatarsal. He wasn’t looking forward to telling his coach.

“I went to Bowerman’s office,” wrote Moore. “All he said to me was ‘You will lay before me the shoes you wore.’”

The shoe in question was not a Bowerman-made shoe but rather the Tiger model TG-22. Bowerman ripped the pair to pieces in front of Moore, discovering the shoe had spongy padding in the heel and under the ball of the foot—but no arch support whatsoever.

“If you set out to engineer a shoe to bend metatarsals until they snap you couldn’t do much better than this,” Bowerman told Moore. “Not only that, the outer sole rubber wears away like cornbread. This is not a shit-shoe, it’s a double-shit shoe.”

Six weeks later, Moore’s foot had healed and he was cleared to run again. This time Bowerman armed him with something different: prototypes with various combinations of cushioning, modified arch support, a heel wedge and an outer sole of firm rubber.

“All the issues with the TG-22 as a running shoe had been addressed,” wrote Moore.

That summer, Moore ran more than 1,000 miles in different versions of those shoes, giving them back for weekly inspections, and then testing prototypes the Onitsuka factory made and sent back to Bowerman for his approval. Early models still had two distinct pads and a heel so narrow that more than a few runners turned ankles. After a year testing and tinkering and exchanging shoes via air mail, the trainer was given the cushioning Bowerman had conceived and a wider heel he favored. Each of those elements was eventually found in the shoe. By early 1967, a catalog description read, “Designed to be the finest long distance shoe in the world. Soft sponge midsole through ball and heel absorbs road shock; high density outer sole for extra miles of wear.”

At the same time that Bill Bowerman’s ideas for Tiger were traveling back and forth across the Pacific, he was also busy putting prototypes on his runner’s feet. Of his own training shoe, Bowerman told Onitsuka that one of his Oregon distance runners had logged more than 1,000 miles.

At the same time Bowerman was working on that running flat with Onitsuka, he was also making recommendations to improve other Tiger shoes, including track spikes. When he requested a thicker sole and wider base for example, Onitsuka was quick to agree and revamp its product.

Despite headway being made on the trainer, Bowerman’s new shoe wasn’t yet in production. Personnel changes at Onitsuka resulted in the departure of his main contact, Morimoto, in the fall of 1965. Bowerman feared progress made on his shoe could be erased.

Much to Bowerman’s relief, H. Fujimoto and Kihachiro Onitsuka were familiar with Bowerman’s shoe, both sending letters on December 23 and December 24, respectively. Kihachiro praised the shoe, prompting Bowerman to respond on January 4, 1966: “It is a great satisfaction to me to know that you were pleased with the experimental shoe which I sent to you and which you made up especially for our runner.”

Bowerman’s innovation went from prototype to a scheduled production model in just one year.

The production of Bowerman’s shoe was timely; the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City was just two years away. In an interview with DNA in 2006, Barbara Bowerman recalled, “[Bowerman and Onitsuka] were very excited when the shoe came out just in time to have them for the Olympics. That was the happiest time of Bill’s experience with the shoemaking business.”

Onitsuka and BRS had ample time to get the TG-24 on the feet of the world’s top runners. But first it would need a more marketable name. At the time, it was customary for Onitsuka to name its shoes after the four major track and field competitions: the Olympics, the Asian Games, the Pan American Games and the Commonwealth Games. Thus, the “Mexico Line” was created in anticipation of the 1968 Olympics.

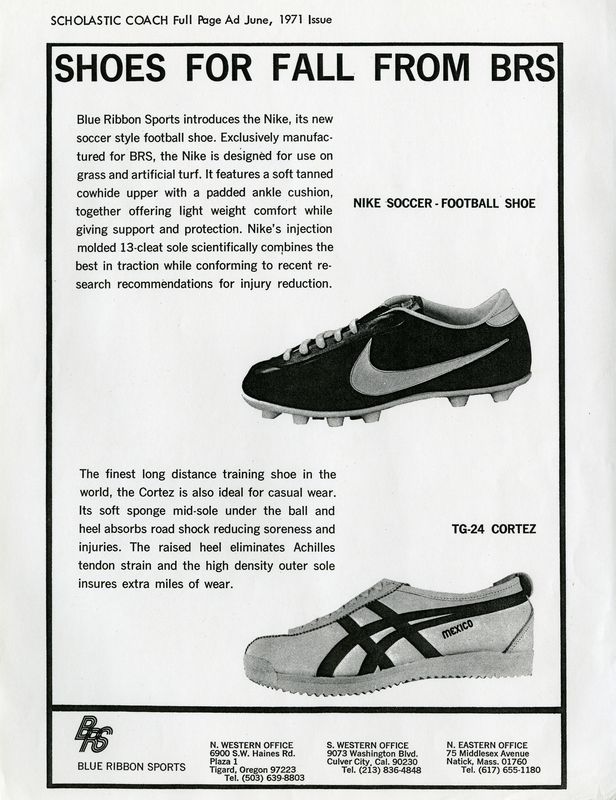

The shoe appeared in a BRS mailer, dated January 30, 1967, with a new name: TG-24 Mexico. Retailing for $9.95, it was accompanied by a description: “The first in Tiger’s Mexico line. This new shoe is a modification of the TG-22 Road Runner, designed for extra miles of wear. Samples tested in the U.S. in 1965 were worn over 2,500 miles.”

By May 1967 however, the shoe was renamed the “Aztec” to complement other shoes in the Mexico portfolio. (A Tiger product line mailer refers to the Aztec as “formerly the ‘Mexico.’”)

The Aztec, which offered a level of cushioning previously unknown to American distance runners, became BRS’s and Tiger’s best-selling training shoe. But it would once again undergo a name change when adidas filed a lawsuit on February 13, 1968, asserting it had already established rights to the Aztec name when it released the Azteca Gold.

Faced with another name change, Bowerman and Phil Knight considered several replacements, with Bowerman focusing on Greek derivations while Knight leaned toward finding a name that evoked a connection to the Mexico Olympics. Still peeved at adidas for making them rename Aztec, they drew their inspiration from the early 16th century Spaniard who conquered the Aztecs: Hernán Cortés.

And thus Cortez was born.

Cortez quickly became BRS’s top-selling running shoe, but it was still evolving, thanks in part to what Jeff Johnson, Nike’s first full-time employee, lovingly referred to as a “crappy 59-cent shower sandal.”

For the first time in a running shoe, the 1968 Tiger Cortez featured a full-length midsole, a concept Bowerman had experimented with while working on TG-24 prototypes. At roughly the same time, Johnson was exploring the same feature as he developed the Tiger Boston running shoe.

A BRS customer in southern California, training for the 1966 Boston Marathon, suggested to Johnson the need for more cushioning. So Johnson, who opened the first BRS store that same year, stitched a shower sandal bottom onto a Tiger TG-4 Marathon shoe. The customer completed the race in the modified shoe even though it lost most of its cushioning by race end. But the marathoner praised its overall comfort.

A few weeks later, Johnson met Bowerman for the first time during the coach’s visit to Los Angeles for a dual track meet between Oregon and UCLA. Johnson seized the chance to speak directly with Bowerman, and, as it turned out, both were working on similar ideas.

“I took one of our shoes to him at the hotel and he was interested in it,” said Johnson of the makeshift running shoe. “He tested them and they compressed because they had that crummy flip-flop midsole material, but he understood the potential.”

Johnson is matter-of-fact about the full-length midsole he developed for the Boston shoe appearing first in Bowerman’s Cortez. Johnson realized Bowerman had the direct line to Onitsuka and the hot-selling Cortez would receive top priority. By late 1969, Tiger delivered the Boston with a full-length midsole as well (which Johnson proudly noted “actually won the Boston Marathon in 1971 on the feet of Alvaro Mejia from Colombia.”)

The full-length midsole quickly became the industry standard for training shoes. The Tiger Boston would become Blue Ribbon Sports’ top selling shoe of 1969. Overall, the Onitsuka Tiger brand was increasing its share of the running shoe market. By 1971, the Cortez and Tiger Marathon were both named “best racing models” by Runner’s World magazine. BRS and Onitsuka, seemingly, were on a roll. But inside the company, a different story was emerging.

By 1971, the partnership between BRS and Onitsuka was deteriorating. In March, Onitsuka representatives visited Phil Knight in Portland in an attempt to take over BRS. Knight was offered a partnership deal in which Onitsuka would get 51% and Knight and Bowerman would receive 49% ownership. Also, Knight had learned that Onitsuka was actively seeking additional footwear distributors in the U.S., which was a violation of the contract between the two companies.

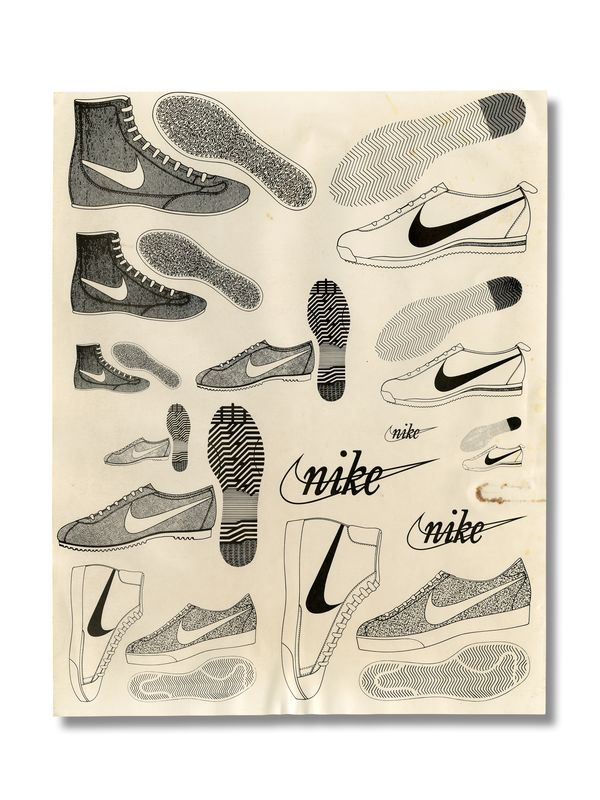

Concurrently, BRS began developing its new Nike line of footwear that would debut for retail the following year. Among its modest offering at the National Sporting Goods trade show in Chicago in February 1972, Nike introduced the Nike Cortez, essentially the same shoe as the Tiger Cortez but with the newly designed Swoosh instead of the Tiger stripes.

On May 1, 1972, Onitsuka informed BRS that it would cease any further supply of Tiger brand running shoes. For Phil Knight and his BRS colleagues, this meant there was no turning back on their new Nike line. The two companies quickly sued each other for breach of contract, with each seeking the exclusive rights to manufacture shoe models like Cortez and Boston. During the months that the lawsuits were being contested, many retailers featured both Tiger Cortez shoes and Nike Cortez shoes, which not surprisingly caused confusion in the marketplace.

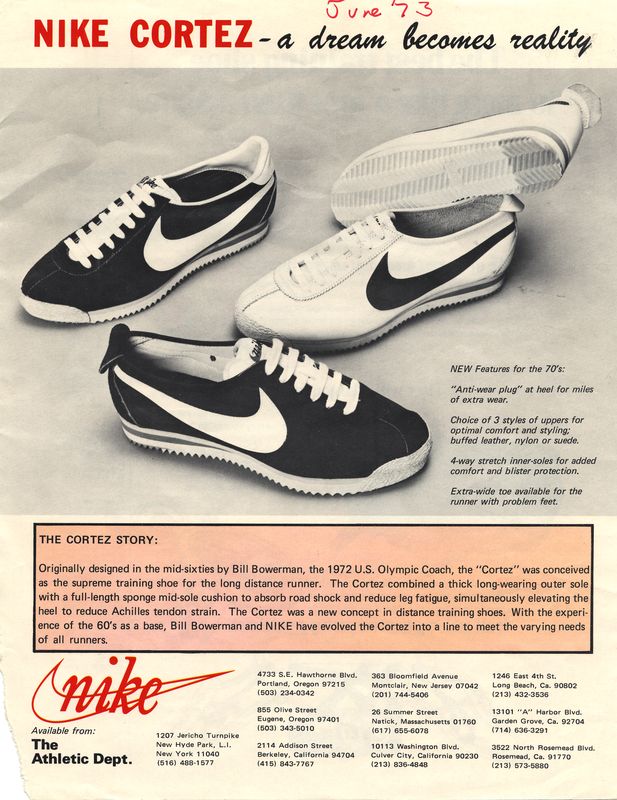

In July 1973, Runner’s World published a booklet, “Shoes for Runners,” and Cortez was still front and center. Since the last survey in ‘71, the running shoe market had changed dramatically, spurred by the entrance of BRS’s Nike brand. So, when Runner’s World called the Nike Cortez “the most popular long-distance training shoe in the U.S,” it was clear a transformation was underway.

The battle over “custody” of the name Cortez persisted. Clearly, whatever company won the rights to the shoe would also gain a substantial foothold in the market. The trial, which took place in April 1974 in US District Court in Portland, ultimately resulted in a victory for Blue Ribbon Sports after all appeals were overruled on July 4, 1975.

The judge ruled it was impossible to untangle who owned the design rights to the shoe models, but that BRS had the exclusive rights to the names of the models. Tiger renamed its version of the Cortez to Corsair, but the basic shoe chassis was the same as the Nike Cortez.

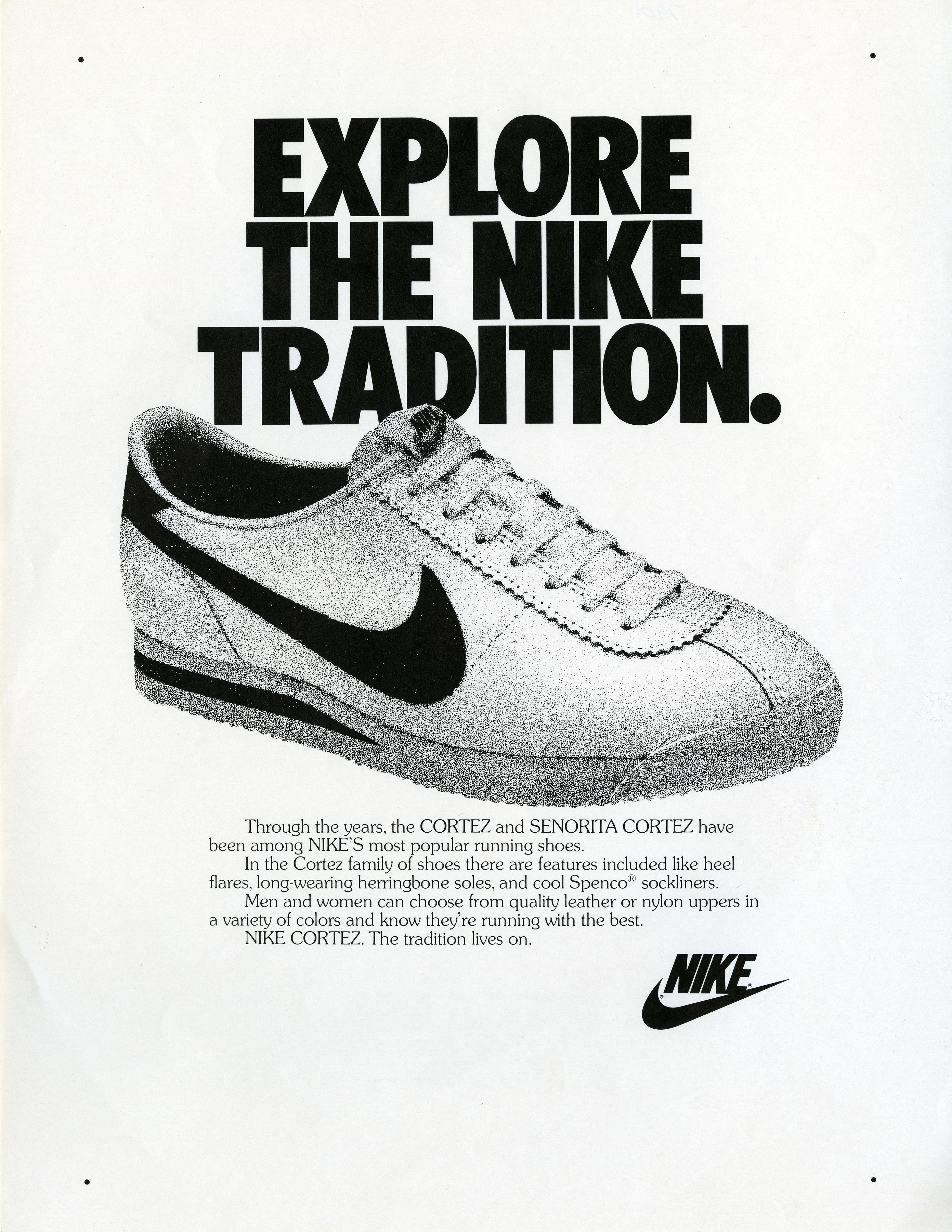

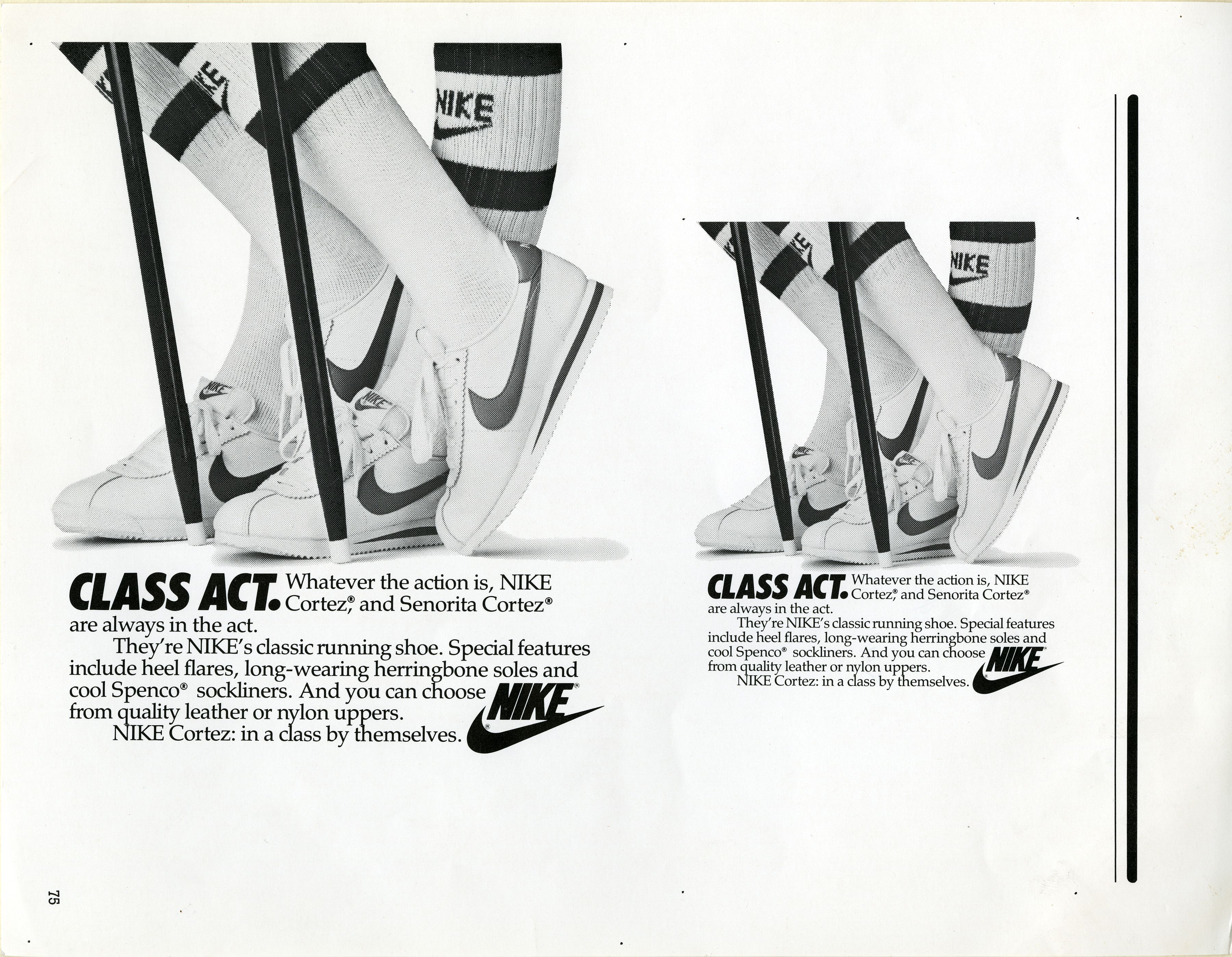

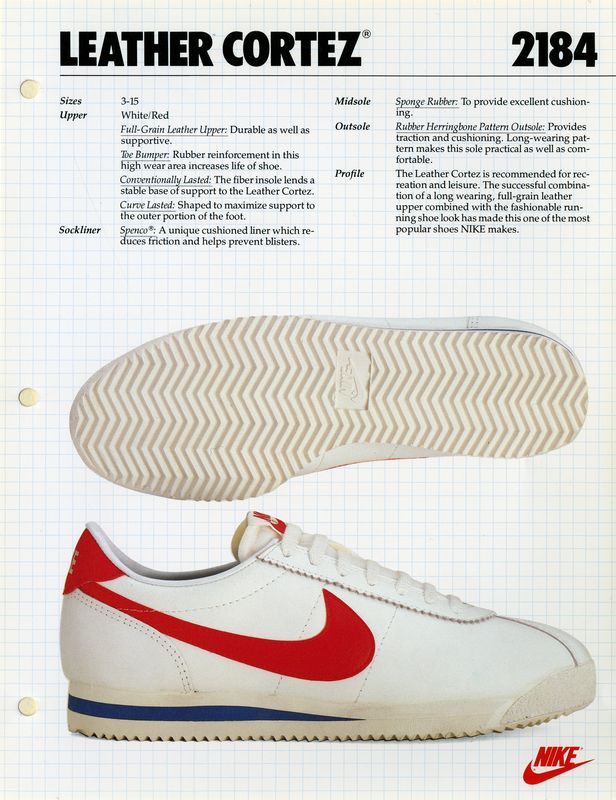

Since its inception, Nike Cortez has evolved over the years and broadened its appeal. The Cortez Deluxe, released in 1973 in white leather and blue suede, featured a wider heel and a heel counter for stability. The Señorita Cortez, made for women, debuted in 1974. Leather Cortez remained the best-selling Nike model through the mid-1970s.

During those glory days of the Cortez story, Nike was also pushing forward, creating new shoe models with innovation even more attuned to runners’ needs. By 1977 the Nike Waffle Trainer and LD-1000 replaced Cortez and Corsair in the Top 25 training shoe list compiled by Runner’s World. Although it was no longer a favorite among runners, Cortez remained popular with general consumers. Declared the magazine: “Sadly, the reliable old shoe is outclassed—in everything but sales.”

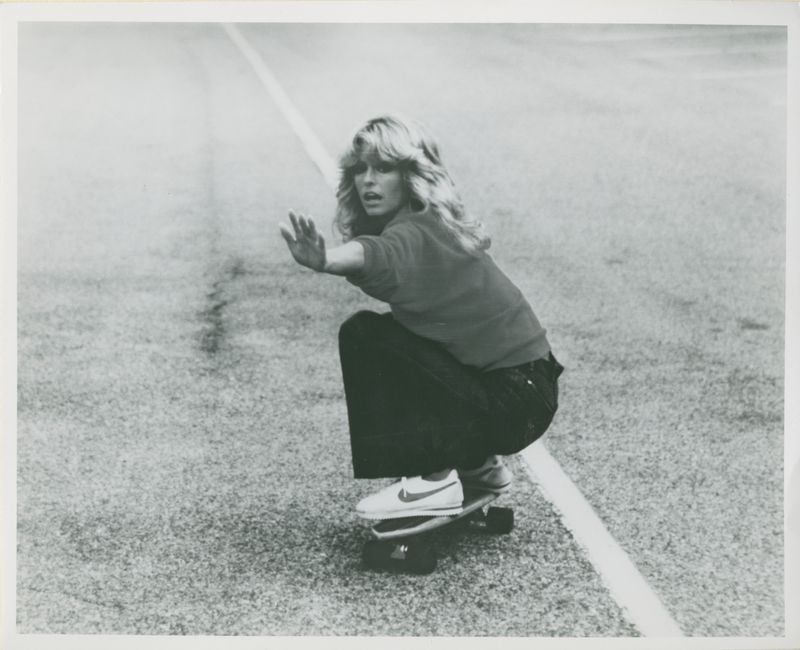

Those ’77 sales of Cortez received a jolt thanks to some unexpected media exposure. During an episode of the popular TV series Charlie’s Angels, 1970s icon Farrah Fawcett wore Cortez as she escaped a bad guy aboard a skateboard, which marked Nike’s entrance into entertainment marketing and correlated with a bump in sales.

Fawcett’s footwear of choice found its role on the big screen as well, most notably in Forrest Gump, 1994’s Academy Award winning Best Picture. The film opens with Forrest (played by Tom Hanks) sitting at a bus stop. A feather once aloft gently falls atop his Nike Cortez, which will later propel Gump on a cross-country run in one of the movie’s pivotal scenes.

For more than 40 years, Cortez has remained a steady performer in Nike’s lineup, now available in the Nike iD and Sport Culture focus areas. Cortez has been produced in school colors, laser-etched and customized for World Cup and the Olympic Games. Corky Cortez was a hit in children’s sizes during the early 1980s.

The Nike Cortez 2 was enhanced by the addition of an EVA midsole in 1988. Flywire technology found its way to the shoe in 2009 with the release of the Nike Cortez Fly Motion. The Nike Cortez NM QS Pack, released in 2013, took the simple upper and gave it a ride on a slitted, sportier outsole.

As the Cortez celebrates more than four decades of life and has evolved to become a throwback design that harkens to Nike’s early years, it’s important to remember that the shoe—and Bowerman’s design acumen—pushed the industry forward. The Cortez was a lightweight running shoe that provided extra padding for the ball of the foot and more cushioning in the heel. Its heel wedge helped ease strain on the Achilles tendon. A thick herringbone outsole provided traction and durability. And its full-length midsole became an industry first.

“He thought that running shoes could be better,” Jeff Johnson said about Bowerman’s early innovations. “He challenged accepted notions of traction, cushioning, biomechanics, and even of anatomy itself.”

The Cortez, Bowerman’s masterpiece, set into motion the influence of creativity while putting athlete’s needs first, a practice still guiding Nike innovation today. “A shoe must be three things,” Bowerman once said. “It must be light, comfortable and it’s got to go the distance.” In many ways, the Cortez fit the bill perfectly.

Our summer ’17 selection of Nike Cortez is available online here and in all size? stores now.