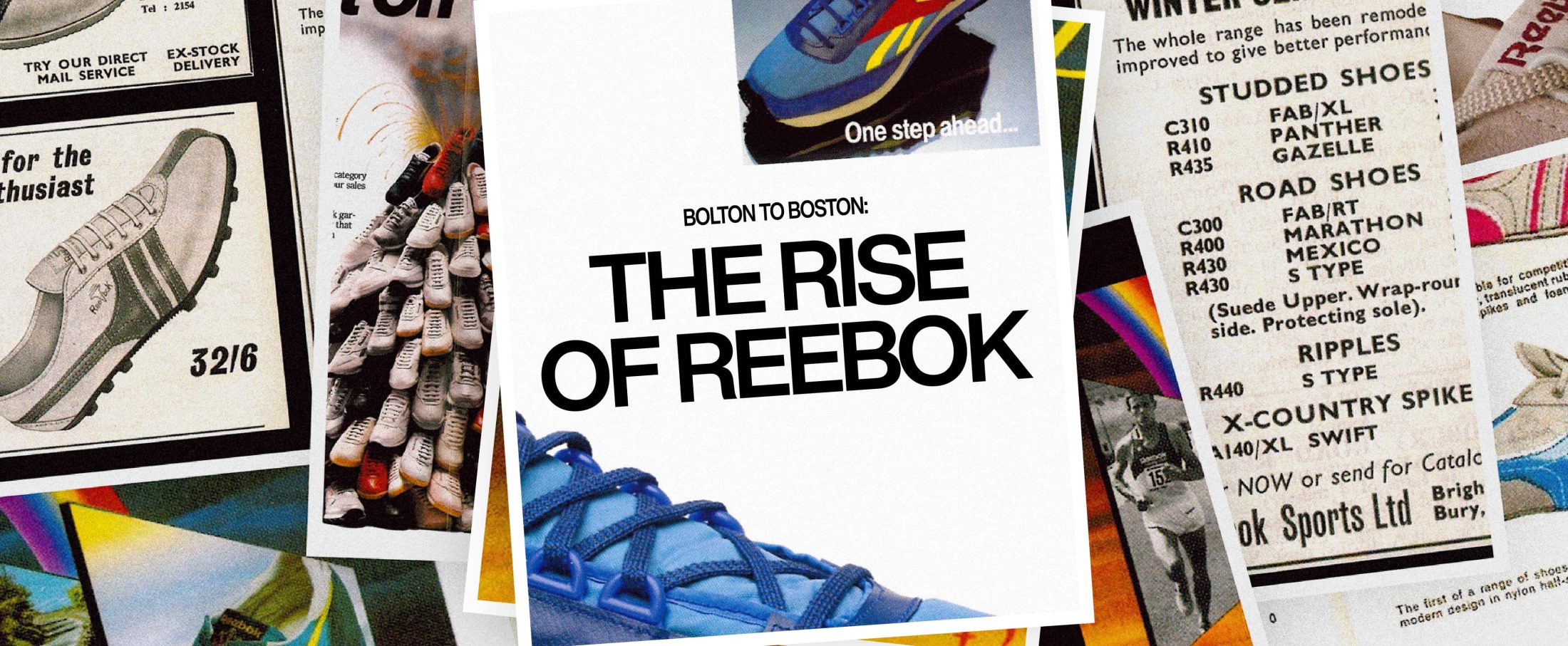

An introduction to Champion Sportswear – Written by Gary Warnett

Some of the greatest clothing brands experience significant demand in a realm they never necessarily sought to reach — think Timberland, Polo and Carhartt — because they inadvertently tap into some element of style that resonates with a generation and the cultures within it, plus the generations that follow. Champion never intended to be the outfitters of every east coast rap video you ever loved between 1991 and 1993, but it just happened that way. That’s not to say that by the time they’d conquered the hearts and minds of a small audience, the brand wasn’t deliberately targeting a wider market.

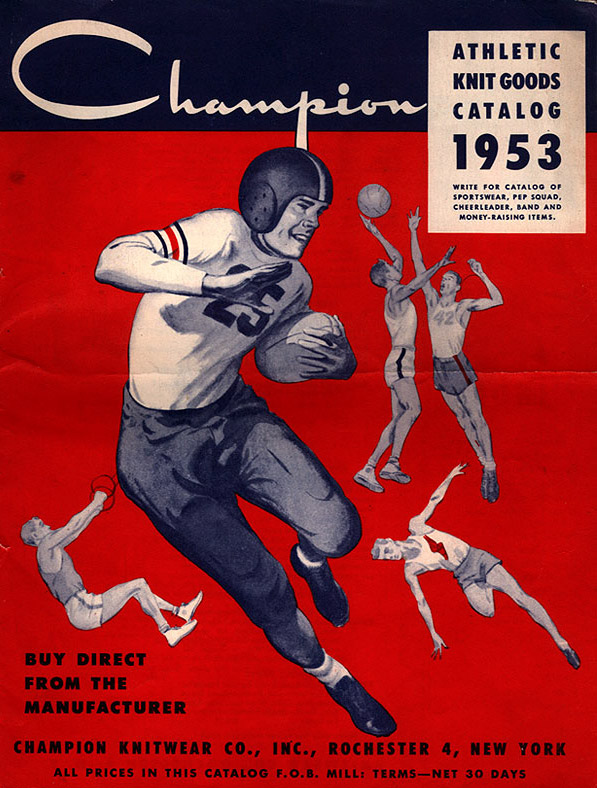

Founded by New York brothers Abraham and William Feinbloom, Champion’s origins lie in the Rochester-based Knickerbocker Knitting Company that opened in 1919. Manufacturing knitted goods, demand for athletic wear led to the Champion collection being sold straight to schools and universities rather than a more conventional mode of retail. In 1923, Champion Knitwear was born — in the years that followed, the company released a number of innovative products. Russell Manufacturing Co. had pioneered the cotton sweatshirt around 1920 (and pioneered a switch from wool to cotton knits for active wear even earlier) to birth Russell Athletic, but the quest to perfect performance design wasn’t over — as part of an occasionally eccentric collection of methods to protect players during training, the hoody was supposedly a Champion invention from a burst of new products between 1930 and 1935.

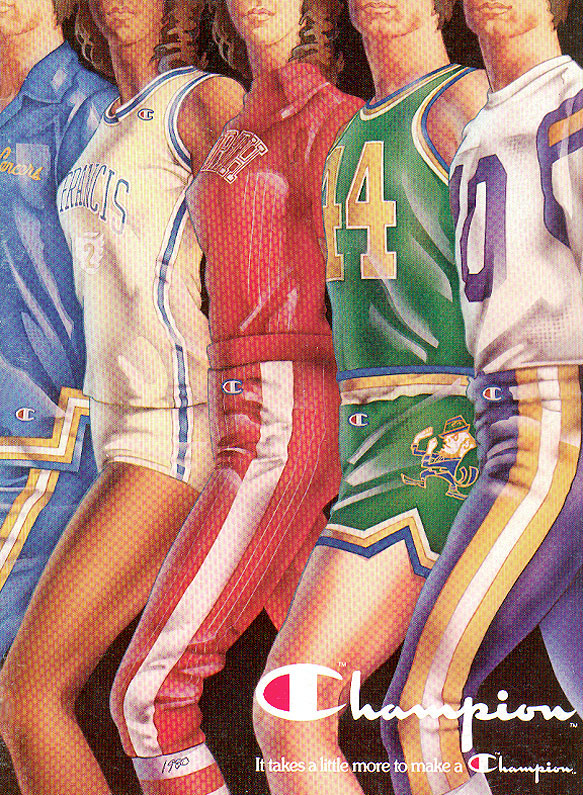

An early 1938 patent from the Champion Knitwear Company Inc. with Samuel N. Friedland as the inventor talks of a method of making athletic shirts with tubular elements and a “horizontal disposition” of threads to minimise stretch and shrinkage. It’s here that Champion’s bestselling Reverse Weave technology was born. A later patent filed in 1951, with Friedland and William Feinbloom credited as inventors, is for the stretch knit side panels on sweatshirts and gussets on sweatpants. Champion would patent methods of letter and number flocking, reversible t-shirts, mesh jerseys, women’s performance wear and screen printing too to stay ahead of the competition and cater to the teams and institutions they were selling to. Champion’s branding would be confined to a label with a gradually evolving set of logos, but it sat the game out in favor of team names and numbers.

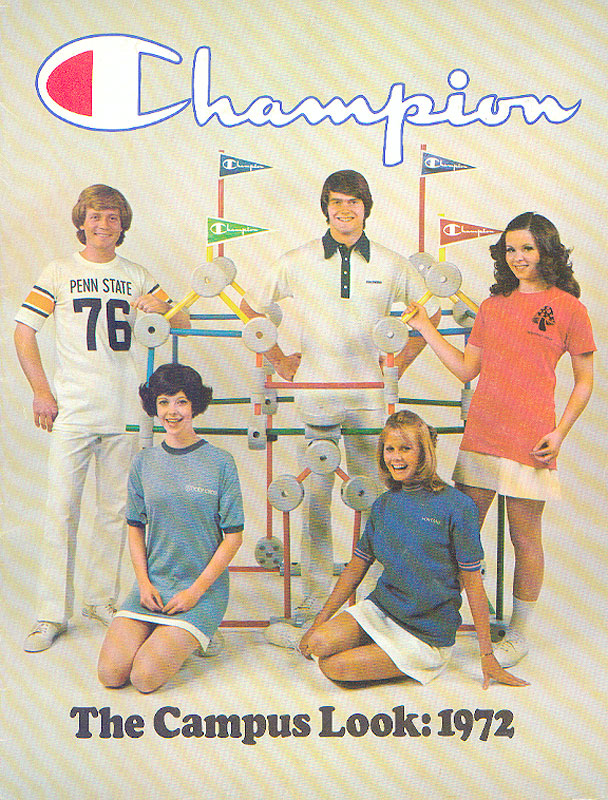

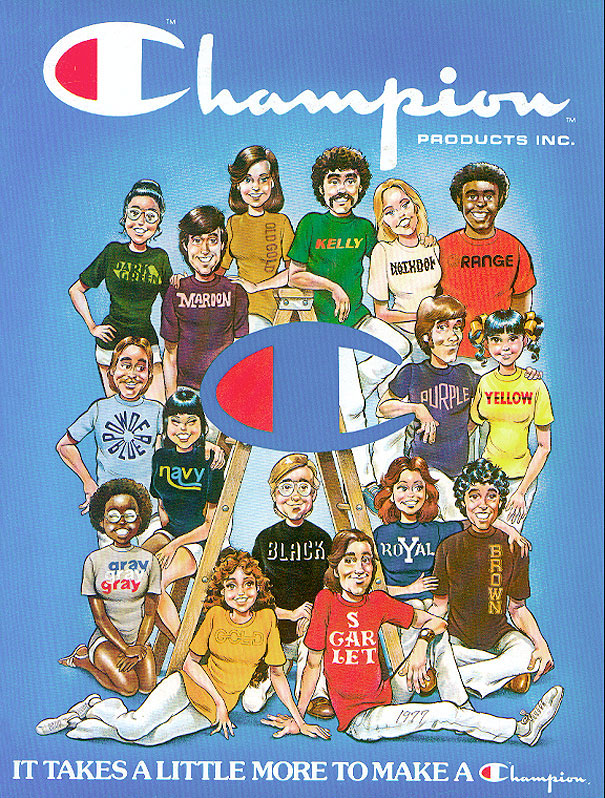

In 1967, the Champion Knitwear company became Champion Products Inc, going public with the Feinblooms as majority shareholders, but securing deals to the identity to Europe and Asia between 1967 and 1977. In the early 1980s, Champion products were sold to stores, with the small C branding as an unobtrusive mark of the product’s origins. The colour offerings grew too. It’s here that the next wave of the interest escalated — when Sara Lee bought Champion in 1989, the distribution expanded significantly, but Reverse Weaves were still a core piece. In 1989, Champion would become the league’s sole outfitter — a savvy move that correlated with a golden age for the game.

It’s strange to think that the buyout — from a company we Brits are more likely to associate more with cakes — would maintain desire for the brand, but it become a phenomenon in the U.S. in the early 1990s with both young and old consumers and the Polo name is incurred on more than one occasion in media reports of the time discussing that popularity, relating to both small branding and social status.

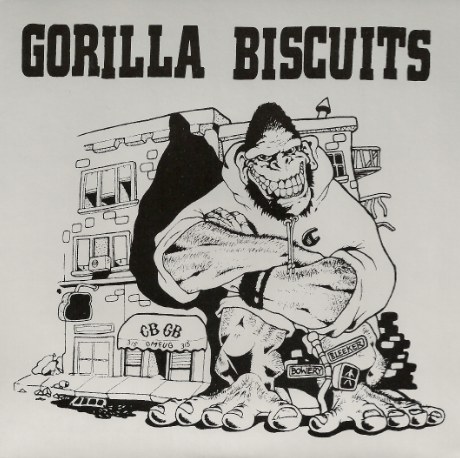

In the late 1980s Champion would become an unofficial outfitter for any straight-edge hardcore group you care to name as hoodies, sweats, tees, shorts and windbreakers were standard issue, with the C making a notable appearance on the artwork for 1988 self-titled 7″ debut from seminal band, Gorilla Biscuits. While it’s often connected to hip-hop, Champion’s status in these scene was far more pronounced — even a decade on, cult west coast straight edgers Champion included a tribute to the brand’s lettering on their demo tape packaging.

Exactly when Champion became synonymous with hip-hop is a mystery — Houston legends the Geto Boys (back when they were Ghetto Boys) wore the brand’s tees and even their sneakers on the cover of their Be Down single in 1988. With the Wu-Tang Clan, Onyx, Lords of the Underground and Gang Starr (Guru even appeared in what seemed to be an official Champion photoshoot or video for the brand in 1993) wearing the brand in an array of colours, with large embroidered scripts, the C on the chest or, occasionally, nothing but a sleeve C, the choice to go colourful like Rakim in the orange hoody or switch to something neutral was there. That these garments were made for jocks meant a voluminous fit was guaranteed — helpful during the era when baggy was the only way to wear a sweatshirt and hip-hop’s influence on fashion was escalating.

Some pieces of Champion’s late 1980s and early 1990s footwear tapped into an aesthetic that was particularly popular in the UK, mid cuts in block colours of suede or leather — blues, greens, reds and yellows. Pieces like the Equinox Hi resemble the Ewing line of the time for a reason — PONY founder Roberto Muller, who was also key to the Ewing line’s launch also handled the Champion footwear license.

Skate culture (especially the east coasters during the gloriously militant early 1990s era) would also embrace Champion sweats for their affordability, loose fit, status and hip-hop affiliations (video soundtracks for classics like Skypager and Virtual Reality were strewn with uncompromising bass and horn led tracks from the era). Larry Clark’s 1994 photography that led to Kids captures Leo Fitzpatrick and co in some vast basic crewnecks with the small signifying C. Washington D.C’s own Chris Hall had an Underworld Element deck with a graphic that homaged the logo.

Post 1995, Champion’s cultural position seemed to slip in favour of other brands, but for those who knew, the C was still a mark of style. Now, in the era of the x (and we’re not talking straight edge this time), printing on a Champion blank can be mistakenly labeled a collaboration, but back in the early 1990s it was just another option for a tee or sweat like Hanes (who Sara Lee took over in 1979 when they were called the significantly more corporate-sounding Consolidated Food Corporation) or Camber — thus early Supreme products came out with the C embroidered on the sleeve and Japanese lines like Good Enough and BAPE opted for Champion as a blank.

Those licensing deals secured in the 1970s bore their on fruits overseas — in Europe, Champion’s position took a distinctly colourful Euro athletic look that became briefly popular in the oneupmanship world of casuals and a post-Paninari realm of expensive apparel. Some Euro pieces like print scripts never had as much visual power or tactile appeal as the stateside offerings, but the global sprawl of the company’s output was impressive.

In Japan however, the preoccupation with Americana made it the greatest use of the license — superseding its country of origin in quality — as Champion was treated as a premium brand. That meant American-made product as well as Japanese-made pieces delving into the archives to amplify that post WWII obsession with U.S. work and sportswear. Faithfully reproduced Reverse Weaves in sizes slimmed for Asian consumers and the T1011 tee stocked in Oshman’s (a Tokyo outpost of an American sports store chain that stocked Reverse Weaves in the 1980s that’s pretty much all gone in the States) could well be the instigators for the current reissues of the brand overseas, treating it with a little more purity and understanding of the Feinbloom’s intent.

Beyond the reverence for the brand here, it’s worth mentioning that — especially after Sara Lee sold the European rights in the early 2000s and HanesBrands took over Champion around 2006 —not everything bearing the Champion logo has been memorable. American made sweats have way to Mexican made versions assembled from U.S. components. To see the branding on bootleg Air Max 1s in an NYC store window or on bargain packs of socks and boxers was proof that the brand was simply a collection of licenses rather than a focused expression of the brand, with a world headquarters pushing for quality control and a single message. Finding certain Champion pieces in the UK became near impossible during the 2000s.

Before Champion’s American wing were working with the likes of Todd Snyder, a late 2000s resurgence on the hip-hop side helped jumpstart the brand at street level again. The Super Hood design, with its exaggerated take on what Champion created almost 80 years earlier, was worn by 50 Cent, Fat Joe, Ghostface Killah, Jadakiss and others — big hoods for hood rap. Champion would introduce the big C designs, with a flocked, amplified version of the C embroidery, possibly as a response to Polo’s big horse pieces. Clearly aimed at a trend audience rather than athletes, Champion even worked with NORE to create a commercial using the Ron Browz produced Rotate in a Champion Hoodie Remix form as Champion was represented as the antithesis of the dressier, slimmer style entering the rap realm.

Adding to the resurgence of the brand, Supreme’s relationship with HanesBrands led to Champion for Supreme pieces that were made to Supreme’s specifications — connecting both brands more officially after those early, anonymous days of using them as the basis for screenprints and sewn letters. Supreme’s ability to straddle several subcultures — from skate to high fashion with a healthy respect for the NYC aesthetic of the brand’s 1994 origin year shouldn’t be overlooked. Basics as well as the big C (available in the UK for the first time via this collaborative arrangement) were part of the regular seasonal rollout.

Our complete Champion apparel collection is available online here and in selected size? stores now.